From the Chicago Reader (November 16, 2001). — J.R.

Tape ***

Directed by Richard Linklater

Written by Stephen Belber

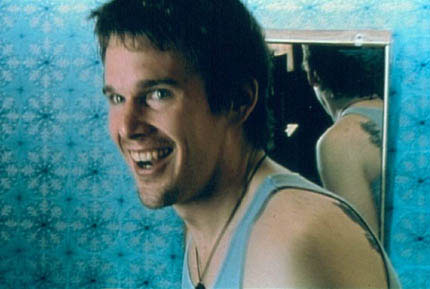

With Ethan Hawke, Robert Sean Leonard, and Uma Thurman.

It seems that the less we know about a subject, the likelier we are to be assertive about it. And journalists play a big role in making people feel knowledgeable about what they don’t know. That’s why we keep encountering more and more twaddle about the state of world cinema even though the growth of digital video makes it impossible for anyone to keep up with the state of local cinema in any large city, much less any country, still less the world. All journalists can honestly say is that more and more works are being made and that keeping up with them is no longer possible. It was only days after an Iranian friend and I completed a book about Abbas Kiarostami that a New York critic E-mailed us about two new Kiarostami works we hadn’t even heard of — a ten-minute short for an episodic feature and a fiction feature in DV that he’s in the final stages of editing.

DV equipment is so easy to shoot with –it’s compact, light, inexpensive, unobtrusive — that it’s hard to keep up with how filmmakers are using the technology. And because the medium is still being explored and tested — by viewers as well as artists — it’s hard to evaluate DV features. That’s why I disagree with Armond White’s recent complaint in the New York Press that Richard Linklater’s Tape — his second DV feature to be released this fall — looks terrible, though it might appear that way if you’re looking for something shot on, rather than transferred to, 35-millimeter. Obviously expectations have a lot to do with such judgments, but what are we saying if we criticize pencils or charcoal over paint and brushes, especially if a sketch is what the artist is after?

Part of what’s off-putting about Linklater’s live-action Tape is how different it is from his animated Waking Life, which was released a few weeks ago. Both are talky, but Tape lacks the humanist aspect we generally expect from Linklater, insofar as none of the film’s three characters is particularly sympathetic. In a way he prepared us for this by linking Tape in some of his interviews to Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope — another film based on a play with predatory characters that’s set in one room and unravels in real time. This led me to expect a film with minimal editing, but it’s far from that; as an exercise in analytical découpage — the French term for a “breakdown into shots,” which effectively combines the meanings of mise en scène and editing — it shows Linklater’s unmistakable flair for interpreting and inflecting the story’s main lines of force as well as its dramatic peaks and valleys, for slithering around the characters to frame them from unorthodox angles, and for briskly swinging back and forth between them in aggressive whip pans. (The whip pans have irritated many reviewers, who apparently expected Linklater to chill out around these unpleasant people.) It’s an intimate way of framing people who claim to be intimate with one another but are really, spiritually speaking, miles apart: that’s the paradox this movie is concerned with, and it works endless variations on the idea.

The play it’s based on is by Stephen Belber, who also wrote the adaptation, and I confess I’d care less about it if Linklater hadn’t used it as a libretto for his découpage — as an occasion for a frenetic workout. Other reviewers have made allusions to LaBute, Mamet, and Pinter, but I’d be more inclined to call this material slacker Strindberg, except that only one of the three characters — albeit the most important one, Ethan Hawke’s Vince — qualifies as a slacker. (More specifically, he’s a drug dealer whose principal clients are middle-aged hippies and firefighters in Oakland.) Strindbergian seems more applicable given the nasty power struggle between the sexes in which both sides come off rather badly. But this characterization is far from complete. There’s also a nasty power struggle between Vince and his “best” friend since high school, John (Robert Sean Leonard), a small-time filmmaker who’s about to show a feature at a festival in Lansing, Michigan, where the film’s action is set. The movie is mainly concerned with this struggle, and the woman, Amy (Uma Thurman), is the focus of it, even though she turns up relatively late in the action. She’s the former girlfriend of Vince, though she never had sex with him, broke up with him senior year, and then had sex with John shortly afterward, and she’s the main threat to their pretense of friendship.

It didn’t occur to me until I saw Tape a second time that it has the same existential theme as Waking Life: truth is unknowable and the only reality anyone can be sure of is subjective. The ramifications of this theme are metaphysical in Waking Life, where the principal issue is whether the protagonist is awake or asleep. They’re mainly ethical in Tape, which hinges on the nature of the sex John and Amy had ten years earlier. Vince is convinced John raped her and goads him into admitting it, then into apologizing to Amy — who now works as an assistant district attorney in Lansing and has been invited by Vince to join him and John that evening.

In both Waking Life and Tape the story is more exploratory and inquisitive than conclusive about the various characters and issues, but even though we can’t determine the precise nature of John and Amy’s sexual encounter, the ethical issues aren’t left open-ended. The question becomes which character and which subjective version of the truth will ultimately be respected the most and therefore be allowed to prevail — and that’s where the Strindbergian power struggle comes in.

The opening sequence is the only one that shows a character alone; strikingly captured, it reveals the divided nature of Vince so starkly that everything else in the action seems to flow logically from it. (The film’s two DV camera operators are Linklater and Maryse Alberti, who’s one of the great cinematographers of American independent cinema; she also filmed Crumb.) The first shot is a hip-level close-up of a beer can being emptied into a bathroom sink; the second is an overhead shot of Vince emptying that can with his right hand while guzzling beer out of another can with his left; and the next three, alternating close-ups and long shots, show Vince crushing the can in his right hand and tossing it into the adjoining motel room, where it bounces and rolls toward the camera at floor level at the same time that he enters the room. After stripping down to his boxer shorts, he repeats the same ritual with two other beer cans, this time throwing one of the empty cans directly at the front door, then does push-ups with his feet on the nightstand and his hands on the floor.

What are we to make of this behavior? When John arrives shortly afterward, we quickly learn that Vince’s girlfriend of the past three years has just split up with him; he isn’t very lucid about the reasons, apart from citing her complaints about his “violent nature.” He mainly denies that he’s violent, though John insists he is. We also learn that she might reconsider if he “keeps going to meetings,” presumably for alcoholism or some other form of substance abuse. John, staying across town at the swanker Radisson, keeps advising Vince like an older brother to clean up his act, but it gradually emerges that Vince considers him a hypocrite and has apparently come to town mainly to expose him. If these guys are best friends, one wonders whom they’d classify as their worst enemies. Viewers might decide early on that, apart from morbid fascination, there’s no clear reason to stick with these creeps; Vince spends most of his time reacting to John’s yuppie hauteur, while John reacts to Vince’s studied oafishness. But Hawke and Leonard do fine jobs of making them seem not only believable but typical: partners in a competitive relationship built on mutual abuse.

By the time Thurman’s Amy enters the action, we’re ready for someone to put each character in his place. She certainly succeeds in doing that, but she winds up coming off only slightly better than they do — no surprise given that she chose to hang out with them ten years earlier. Half a century ago most viewers scoffed at the French critics who called Alfred Hitchcock a stern moralist, but nowadays it’s hard to see him as anything else. Giving Linklater such a label may seem difficult, but look closely at the personal anguish about the battered innocence of a high school senior underlying his Dazed and Confused (1993). Tape — whose opening credits play over the sound of an audiotape being rewound — may ultimately qualify as an act of self-psychoanalysis, however veiled, much as Rope did for Hitchcock in 1948, and a DV camera and a tape recorder (the movie’s pivotal prop) are vital tools in this endeavor. Consciously or not, an experiment in technique seems to function as the pretext for a rigorous self-scrutiny and autocritique.