Commissioned and published online by BBC.com in November 2018. — J.R.

Luis Buñuel was the greatest of all Spanish film-makers. He is also known as the greatest of all Surrealist film-makers – someone who kept returning to dreams and the unconscious, all the way from Un Chien Andalou, the silent avant-garde shocker he made with Salvador Dali, to Belle de Jour, in which sado-masochistic fantasies lurk beneath Catherine Deneuve’s chic surface. It’s no wonder that in critical studies of his films, the emphasis is on Freud as a “guide” to Bunuel’s greatness. But the influence of another thinker, Marx, was just as important. However surreal Bunuel’s work may be, political revolt and an acute feeling for class struggle informed all of it, whether it was French, Mexican or Spanish.

Truly a child of the 20th century, Luis Bunuel Portoles was born in 1900, the oldest child in a prosperous Catholic family based in the Aragon region of Spain. He first made his mark four years after he moved to Paris in 1925, when he joined forces with Dali to make Un Chien Andalou. Buñuel and Dali began collaborating again on the hour-long L’Age d’or (1930), but their political differences were already driving them apart: Buñuel’s Marxism versus Dali’s conservatism. Buñuel became the sole director of L’Age d’or, a film which ridiculed high society and religious hypocrisy. And after returning to Spain in the early 1930s, he made a short documentary dealing with the extreme poverty in a mountain village, Land Without Bread (1933).

When his anti-Franco activities drove him into exile, he resettled in Mexico, where leftist protest was even more apparent in his low-budget commercial features. Los Olividados, which ranked at number 80 in BBC Culture’s poll, was a compassionate yet pessimistic Marxist depiction of abject poverty and teenage crime in Mexico City that defied any notion of the poor as the salt of the earth while drawing powerfully on Freudian Surrealist imagery to illustrate the tortured dreams and visions of Buñuel’s blighted characters. The other major Mexican works of his that followed — including Mexican Bus Ride (1952), Él (1953), Robinson Crusoe (1954), Nazarin (1959), The Young One (1960), and The Exterminating Angel — all reflected these orientations in their creepy visionary undercurrents and their sharp class distinctions.

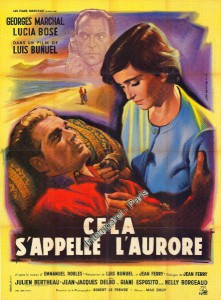

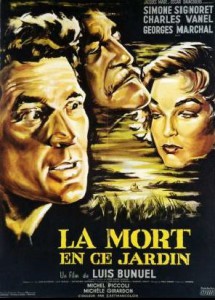

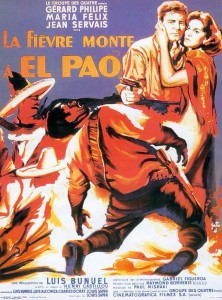

Él, for instance, was a black comedy focusing on a wealthy and paranoiacally jealous newlywed. And Buñuel’s faithful yet personal adaptation of the famous Dafoe novel, Robinson Crusoe, co-written by the blacklisted American screenwriter Hugo Butler, made room for both class issues (in the hero’s interactions with Friday) and Surreal hallucinations. Another neglected jewel co-written by Butler, The Young One, made brilliant use of a setting in the American South to chart the comic interactions between a black musician (Bernie Hamilton) in flight from a rape charge and a randy beekeeper (Zachary Scott) in relation to an innocent teenage girl (Key Meersman). The Exterminating Angel, number 67 in the poll, charted the even funnier complications that ensue when a group of wealthy dinner guests inexplicably find themselves unable to leave their host’s living room. During this same period, Buñuel reflected on his status as an anti-Franco Spanish exile by directing three French coproductions that dealt with issues arising from armed struggle against right-wing dictatorships: Cela s’Appelle l’Aurore (1956), Le Mort en ce Jardin (1956), and Fever Mounts at El Pao (1959).

But the undoubted masterpiece of this period — and arguably the greatest triumph of Buñuel’s career — was Viridiana, his first Spanish feature, in which wealthy and impoverished characters were equally prominent and whose Catholic/Surrealist imagery was epitomized by a switchblade knife in the shape of a Cross. (It ranked at number 48 in BBC Culture’s poll.) Developing the theme of his earlier Nazarin (one of Andrei Tarkovsky’s favourite films) about a despairing priest attempting to exercise charity in an imperfect world, this is the tale of a former novice (Mexican actress Silvia Pinal) who jointly inherits the property of her decadent uncle (Fernando Rey, who became a Buñuel regular) along with his illegitimate son (Francisco Rabal, also the priest in Nazarin), and invites a group of rural beggars to share her property, with disastrous results.

Viridiana caused an immense scandal after winning the top prize in Cannes and being banned in Spain, and this led to the director’s triumphant return to Europe, mostly to make French features. Two of these, Belle de Jour (1967) and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), occupy 75th and 84th place respectively in the poll, and the latter film won Buñuel his only Oscar. After reporters informed him that it was nominated, he replied, “I’ve already paid the $25,000 they wanted. Americans may have their weaknesses, but they do keep their promises.”

Aside from Tristana (1970), his only purely Spanish feature apart from Viridiana, all of Buñuel’s late films were co-written with a French screenwriter, Jean-Claude Carrière. Playing with narrative form more radically (and Surrealistically) than his Mexican and Spanish work, these French films also harked back to the spirit of L’Age d’or by focusing on Buñuel’s own class and by favouring diverse forms of discontinuity, such as narrative interruptions (in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and its 1974 follow-up, The Phantom of Liberty) and using two actresses to play the same heroine in That Obscure Object of Desire (1977).

But the revolutionary aspect was still there. The difference was that, in all of these films, sexual politics figured as another form of class politics. (Even in That Obscure Object…, the two actresses playing the heroine belong to separate classes, complicating the diverse ambiguities.)

Buñuel’s increasing sympathy for his heroines seemed to start in the 1960s, contradicting the macho aggression of his early work (in Un Chien Andalou he appeared to slice a woman’s eyeball with a razor). Carrière has pointed out that when they worked together on their scripts, he typically spoke for the male characters and Buñuel spoke for the women — including the chambermaid (Jeanne Moreau) in Diary of a Chambermaid, the title heroine (Catherine Deneuve) of Belle de Jour, Conchita (played alternately by Carole Bouquet and Angela Molina) in That Obscure Object of Desire.

The last film he directed before his retirement, That Obscure Object … actually anticipates the #MeToo movement by recognizing that male entitlements and class entitlements usually turn out to be densely interwoven. Bunuel may have been a child of the 20th century, but his work remains timely and relevant in the 21st.