When I previously reprinted on this site my first Paris Journal for Film Comment, from their Fall 1971 issue, I omitted the entire opening section, largely because of its embarrassing misinformation (both naive and ill-informed) in detailing the background of the ongoing feud at the time between Cahiers du Cinéma and Positif. But for the sake of the historical record, I’ve decided to reprint it now, along with a lengthy letter from Positif’s editorial board and my reply to it two issues later. — J.R.

Of all the gang wars waged over the past thirteen years between Cahiers du Cinéma and Positif, the latest appears to be the most extensive and the least illuminating. When Truffaut ridiculed Positif for anti- intellectualism and self-serving vanity in 1958, Cahiers‘ orientation was Catholic-conservative while its leading rival was surrealist and leftist; the former enshrined Hollywood while the latter denigrated it as imperialist. When Positif launched a lengthy counter-offensive in 1962 (amply documented in Peter Graham’s anthology, The New Wave), the terms of the equation had already begun to shift: many Cahiers critics were already beginning to veer away from their backgrounds as they became filmmakers, and Positif was starting to develop a stable of its own Hollywood auteurs, like John Huston and Jerry Lewis. After the May Events of 1968, the divergence between the magazines became even sharper, with Cahiers — as it underwent an almost complete turnover of staff — gradually adopting a militantly Marxist-Leninist and structuralist position, and Positif, despite at least one Maoist on its editorial board, opening its pages to lengthy interviews with “counter-revolutionaries” like Chabrol and Frankenheimer. ln 1969, the renovated Cahiers rekindled the feud by recasting some of Truffaut’s arguments and adding the charge of reactionary fake-liberalism.The latest and bloodiest round begins in the December, 1970 issue of Positif, which devotes over a third of its 72 pages to attacks by Michel Ciment, Louis Seguin and Robert Benayoun, accusing their opponents of Stalinism, obscurantism and outright fakery; it is quickly succeeded by angry letters and rebuttals in both magazines.

A few relevant details: from the beginning, Cahiers‘ putdowns have tended to be terse and condescending, Positif’s outraged and endless. A collective statement by the editors of Cahiers, Tel Quel and Cinéthique has appeared in issues of all three magazines, describing Positif’s latest foray as part of a general trend to discredit all “revolutionary theoretical work.” ln large measure, the pivotal focus of Positif’s renewed aggression is the extensive coverage Cahiers has given to Straub’s OTHON; particular rancor is expressed over some of Straub’s willful assertions about the film and Cahiers‘ respectful glosses.

Beneath this rubble of mutual abuse, Cahiers continues to be a magazine of major importance, despite its recent masochistic rites of exorcism (e.g., the collective reconsiderations of YOUNG MR. LINCOLN and MOROCCO, which read like sociological autopsies of previous diseases) and a prose so difficult to crack, even for natives, that a joke was already making the rounds two years ago that the magazine was coming out with a new edition in French; while Positif remains a readable, occasionally useful an insightful journal with somewhat lesser ambitions. Both magazines have been so clique-oriented that for years each had their own “favorite seats” at the Cinémathèque and at times one is tempted to feel that the squabbling on both sides has less to do with films and issues than with the considerable egos involved — another symptom, perhaps, of the suicidal splintering and solipsism built into the reflexes of the French left.

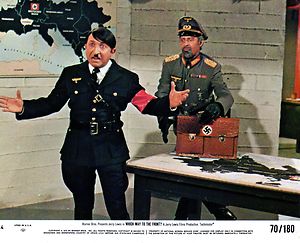

lf the magazines are in agreement about any one subiect, this is the incontestable genius of Jerry Lewis, and recent reviews of WHICH WAY TO THE FRONT? in each magazine may provide a useful index to their personalities. Benayoun’s lengthy discussion in Positif #122 and Serge Daney’s five numbered paragraphs in Cahiers #228 both have their moments of ingenuity.Lewis’ latest film concerns “the richest man in the world,” played by Lewis, a neurotic named Byers who counters his rejection from the draft during World War II by launching an absurd, expensive campaign of his own in Italy, manned by a few other rejects he has bribed, and enacted through his own impersonation of a Nazi general; they succeed in defeating the Nazis and blowing up Hitler single-handedly, and when last seen are busily at work on the Japanese.

Both reviews treat Byers as an analogue to America’s position in the world. Benayoun rather intricately relates the megalomania of the character to that of America and Lewis himself (as writer-director-performer), establishing cross-references with Chaplin’s THE GREAT DICTATOR and Lubitsch’s TO BE OR NOT TO BE; Daney grazes past a few of the same points while tracing a series of puns (Byers = buyers, a character named “General Buck,” etc.) and adding a few strained ones of his own, generally relegating his comments to semi-abstract notations rather than explications Both pieces are recommended to anyone interested in penetrating the French Lewis mystique: as I write in early May, Lewis has just completed a “record-breaking” live engagement in Paris, and his reception has generally been so delirious that one suspects a rapprochement between warring Frenchmen might be possible after all.

***

From Film Comment, Spring 1972:

To the Editor:

In his letter from Paris published in your fall 1971 issue, your correspondent Jonathan Rosenbaum is perfectly entitled to judge as he wishes the current controversy between Cahiers du Cinema and Positif, though we find it amusing that he thinks Cahiers continues to be a magazine of major importance (which Positif in his eyes has never been) while he judges “its prose difficult to crack even for natives.” On what grounds then does he evaluate its importance?

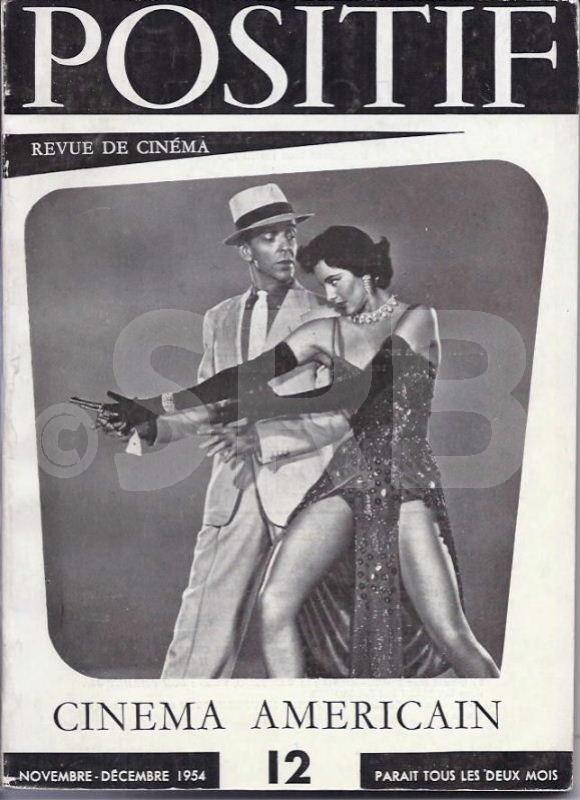

We would just like to correct a major mistake which betrays a complete lack of information. When he writes that, “in 1958 Cahiers enshrined Hollywood while Positif denigrated it as imperialist”, and that “in 1962 Positif was starting to develop a stable of its own Hollywood auteurs like John Huston and Jerry Lewis,” he draws a nice and clear opposition which has no relation whatsoever to the reality. The truth is that as early as the Fifties Positif defended as many young filmmakers (Antonioni, Wajda, Maurice Burnan) as it defended in the Sixties (Marco Bellocchio, Ruy Guerra and Dušan Makavejev). But it dealt with the American cinema in a more complex way than your correspondent would like to make you believe. Then as now, a political stand was taken and our admirations were never uncritical, but if you look at older issues you can easily find a defense of the American cinema and of its popular genres (musical, western, thriller. cartoon) and authors: number 3 (July-August 1952) complete issue devoted to John Huston; number 11 (September-October 1954) complete issue on politics and the American cinema; number 12 (November-December 1954) complete issue on genres with articles on the western, Minnelli, Gene Kelly, animated cartoons, and science-fiction; number 17 (June-July I956) special issue on Richard Brooks; number 20 (January 1957) new issue on John Huston; number 26 (Fall 1958) special issue on Frank Tashlin with an essay on Jerry Lewis; number 32 (February 1960) special issue on Burlesque and essays on Aldrich, Wellman, and Ford.

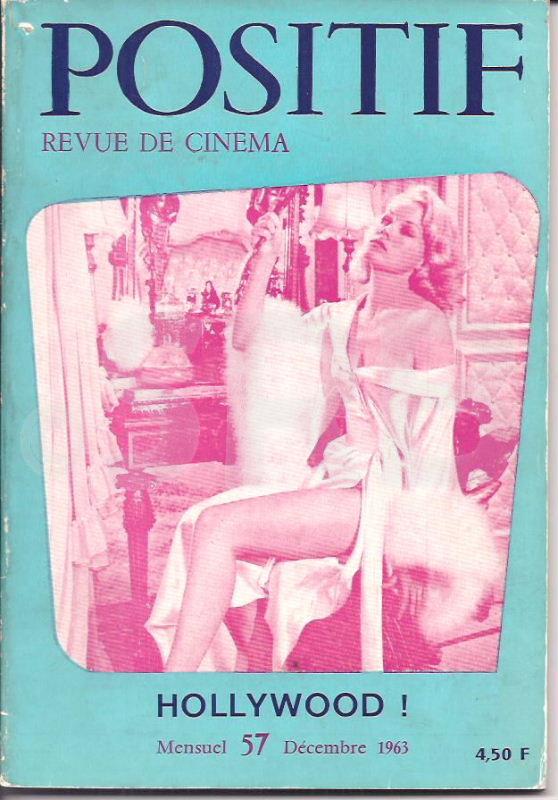

And when we chose for our covers (free from publicity!) DEADLINE USA (number 12), THE BAND WAGON (number 13), PUSHOVER (number 16), BATTLE CIRCUS (number 17), Cyd Charisse (number 20), Dorothy Malone (number 24), Louise Brooks (number 27), HOLLYWOOD OR BUST (number 29), NEVER GIVE A SUCKER AN EVEN BREAK (number 32), it was not to expose them as agents of imperialism!

lf we go into such details, it is not to justify ourselves (informed French readers know all about it), but to correct some mistakes which are currently made abroad where the history of French criticism is not so well known. It is not our role to say whether it is an important matter or not but, as long as it is dealt with, your readers should know some of the basic facts.

We do not claim that in 20 years the magazine has followed a clear and pure line. We admit that some of our attitudes have evolved, some of our judgments have been reconsidered and that we have paid more attention to various filmmakers than we did in the past. But, more than in any other French film magazine, we think that in the 132 issues that we have already published you can see a certain consistency based on a defense of several new talented directors appearing here and there in the world (see for instance the first study on the cinema of Dubrovnia — number 27), a consideration of the sociological and political background which gives birth to the films and of the context in which they are shown, and a constant attention paid to the cinema in its popular genres, which means a great interest in the American cinema. We are far from the clearcut distinction that Mr. Rosenbaum tried to draw for your readers and we would not pay so much attention to this misinformation if it did not appear in a magazine whose standard we have learned to appreciate.

Sincerely yours,

The Editorial Board, Positif

Jonathan Rosenbaum replies:

I apologize to the editors of Positif for over-simplifying my description of some of the magazine’s overall trends, thereby distorting some of its achievements in the process. In order to write about the Positif–Cahiers controversy for an American audience in limited space, a great deal of generalization about the magazines’ respective histories was necessary, particularly since I was discussing them only in terms of contrast. To a lesser extent, the writers of the letter share a similar difficulty when they abridge all three of my sentences that they quote from, and consider them outside of their contexts.

My judgment of the continuing importance of Cahiers largely rests on their contributions to research, such as their double issues devoted to Russia in the 20s (#220-221, 197O) and Eisenstein (#226-227, 1971) and more recently, their translation of a shot-by-shot description of INTOLERANCE. In all fairness, however. I should mention that as an intelligent, dependable chronicler of both current and older films, Positif has lately become quite superior to Cahiers, particularly during the past year.Indeed, whenever the editors find the time to stop laughing at their own rather ancient Surrealist jokes (e.g., their articles on the nonexistent Dubrovnia and Maurice Burnan) and fighting feuds, their services are often useful; their recent issue on Frank Capra (#133) is a case in point.