Written for Cinema Narcissus, a collection put together for the Rotterdam International Film Festival in early 1992….One of the regular visitors to this site, Barry Scott Moore, has reminded me that in 2013, Ehsan Khoshbakht pointed out to me that Lewis’s first use of the video assist was actually in The Bellboy, his first feature. (He also drew my attention to several typos, now corrected below.) — J.R

The total film-maker is a man who gives of himself through emulsion, which in turn acts as a mirror. What he gives he gets back. — Jerry Lewis

It was Jerry Lewis who first had the idea of installing a video monitor on a soundstage while shooting a picture. The feature in question was THE LADIES MAN (1961), most of which was shot on a single set, a four-storey, open-faced building that stretched across two soundstages on the Paramount lot. The reason for this video monitor? To allow Lewis to see what a particular camera setup looked like at the same time that he was acting in the shot.

Directing and acting at the same time in comedies is a practice that can be traced back at least as far as the beginning of the 20th century. Read more

From the Jewish Daily Forward, October 9, 2012. — J.R.

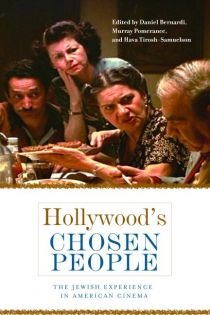

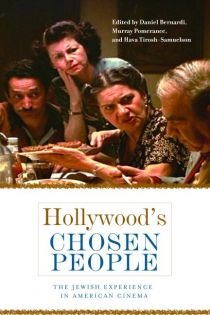

Hollywood’s Chosen People:

The Jewish Experience in American Cinema

Edited by Daniel Bernardi, Murray Pomerance, and Hava Tirosh-Samuelson

Wayne State University Press, 270 pages, $31.95

The coeditors stake their claim in the first sentence of their Introduction: “This book sets out to mark a new and challenging path of the role of Jews and their experience in Hollywood filmmaking.” And to some degree, they live up to this goal, in a varied collection that tends to get livelier as it proceeds. But considering how slippery and elastic their definitions of “Jews” can be, part of their path strikes me as both familiar and questionable.

Fritz Lang, for instance, gets cited over a dozen times in the book’s index, but for me his inclusion is fully justified only once — in a fascinating article by Peter Krämer that charts diverse efforts over four decades to make a movie about Oskar Schindler that preceded Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List in 1993, many of them launched by Schindler himself, who had a lengthy correspondence with Lang about the first of these projects in 1951. Virtually all the other references assume that Lang was a Jew because of his mother’s origins—a default position held in spite of his being raised solely as a Catholic and apparently never betraying the slightest interest in identifying himself any other way. Read more

This essay was originally written as liner notes for a DVD released in 2006 in the U.K. by Second Run, an excellent label. (This DVD can be obtained here—a site well worth checking out for other films as well.) My thanks to Mehelli Modi for commissioning this piece as well as for allowing me to reprint it, both here and in my collection Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia. I’m delighted, incidentally, that Lorber Kino’s recent DVD release of these films also includes not only My Girlfriend’s Wedding and Pictures from Life’s Other Side, but also McBride’s wonderful recent short, My Son’s Wedding to My Sister-in-Law (2008). — J.R.

In my mind, there isn’t as much of a distinction between documentary and fiction as there is between a good movie and a bad one. — Abbas Kiarostami

Artifact #1: A softcover book, The Film Director as Superstar (Garden City, NY:

Doubleday & Co.,1970)—-a collection of 16 interviews in three parts, each of

which has two subsections: “The Outsiders” (”Beyond the Underground,” “Their

Own Money, Their Own Scene”), “The European Experience” (”The Underemployed

Independent,” “The Socialist Film Schools”), and “Free Agents Within the System”

(”Transitional Directors,” “Independents with Muscle”). Read more

From the October 21, 2005 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Good Night, and Good Luck

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by George Clooney

Written by Clooney and Grant Heslov

With David Straithairn, Clooney, Robert Downey Jr., Patricia Clarkson, Frank Langella, Ray Wise, Heslov, Jeff Daniels, and Dianne Reeves

Capote

*** (A must see)

Directed by Bennett Miller

Written by Dan Futterman

With Philip Seymour Hoffman, Catherine Keener, Clifton Collins Jr., Chris Cooper, Bruce Greenwood, Bob Balaban, Mark Pellegrino, and Amy Ryan

Good Night, and Good Luck and Capote view journalism as an intricate mix of principles, bravado, and negotiation. Working in a minefield, their star journalists are victims of their vocations. Good Night, and Good Luck, set in the early 50s, celebrates Edward R. Murrow’s bravery, eloquence, and sense of justice in challenging Joseph McCarthy at the height of his power — a kind of heroism that evokes John Wayne’s in a western like Rio Bravo (a movie I cherish, though its view of good and evil is similarly unshaded). Good Night, and Good Luck — named for Murrow’s sign-off line — also explores how internal politics at CBS were shaped by the network’s relations with its sponsors. The victimization of Murrow can be seen in his early death from lung cancer — his chain smoking, like James Agee’s and Albert Camus’, was somehow connected in the public mind with his moral seriousness — and in the way his weekly show, See It Now, was bumped to a Sunday-afternoon slot after he challenged McCarthy. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 13, 2006). — J.R.

Infamous **

Directed and written by Douglas McGrath

With Toby Jones, Daniel Craig, Sandra Bullock, Jeff Daniels, Peter Bogdanovich, Sigourney Weaver, and Hope Davis

Two recent features about Truman Capote, coincidentally made around the same time, concentrate on Capote’s work on his true-crime best seller In Cold Blood, about the slaying of a family in rural Kansas. Both suggest that Capote’s life and career were destroyed by the emotional strain of researching and writing that book, yet they’re fascinatingly different in what they try to do and in how they depict their subject. Capote — which professes to be based on Gerald Clarke’s standard biography of the same title — came out a year ago and won its lead actor, Philip Seymour Hoffman, an Oscar. Infamous — which claims to be based on George Plimpton’s Truman Capote, a collection of gossipy sound-bites assembled in the same manner as his “oral histories” about Edie Sedgwick and Robert F. Kennedy — was released a year after it was completed to avoid comparisons with Capote. Now that it’s out, comparisons are in order — and not all of them are to Capote‘s advantage. Read more

Originally written as the tenth chapter of my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000), this is also reprinted in my 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles. Because of the length of this essay, I’m posting it in two installments – J.R.

3. The taboo against financing one’s own work. I assume it’s deemed

acceptable for a low-budget experimental filmmaker to bankroll his or

her own work, but for a “commercial” director to do so is anathema

within the film industry, and Welles was never fully trusted or respected

by that industry for doing so from the mid-forties on. This pattern

started even before Othello, when he purchased the material he had

shot for It’s All True from RKO with the hopes of finishing the film

independently, a project he never succeeded in realizing. As an

overall principle, he did something similar in the thirties when he

acted in commercial radio in order to surreptitiously siphon money

into some of his otherwise government-financed theater productions

during the WPA period, a practice he discusses in This Is Orson

Welles. John Cassavetes, who also acted in commercial films in order

to pay for his own independent features, suffered similarly in terms of

overall commercial “credibility,” which helps to explain why he and

Welles admired each other. Read more

Originally written as the tenth chapter of my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000), this is also reprinted in my 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles. Because of the length of this essay, I’ll be posting it in two installments – J.R.

Nothing irritates one more with middlebrow morality than the perpetual needling of great artists for not having been greater.

— Cyril Connolly

During my almost thirty years as a professional film critic,

I’ve developed something of a sideline — not so much by

design as through a combination of passionate interest and

particular opportunities — devoted to researching the work

and career of Orson Welles. Though I wouldn’t necessarily

call him my favorite filmmaker, he remains the most

fascinating for me, both due to the sheer size of his talent, and

the ideological force of his work and his working methods.

These continue to pose an awesome challenge to what I’ve been

calling throughout this book the media-industrial complex.

In more than one respect, these two traits are reverse sides of

the same coin. A major part of Welles’s talent as a filmmaker

consisted of his refusal to repeat himself — a compulsion to

keep moving creatively that consistently worked against his

credentials as a “bankable” director, if only because banks rely

on known quantities rather than on experiments. Read more

From the December 7, 2001 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

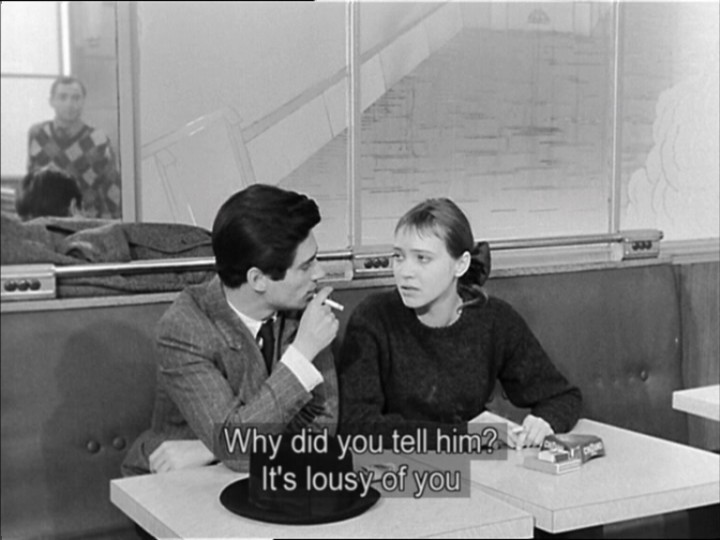

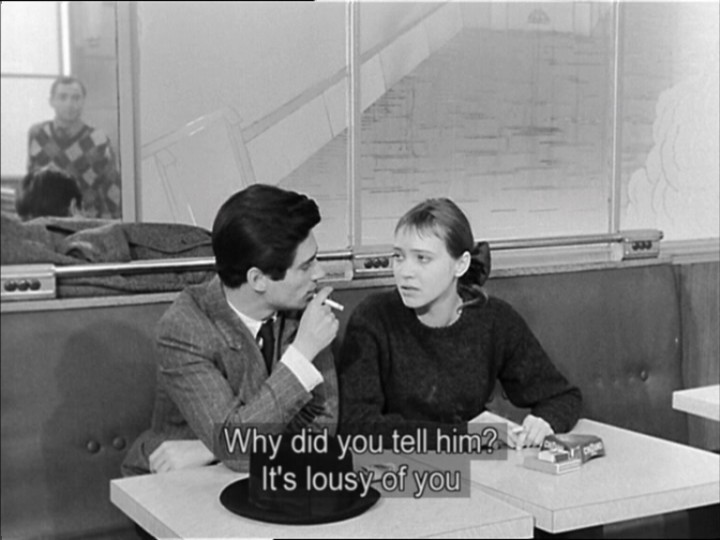

Band of Outsiders

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Jean-Luc Godard

With Anna Karina, Claude Brasseur, Sami Frey, Daniele Girard, Louisa Colpeyn, and Ernest Menzer.

To gauge the historical significance of Jean-Luc Godard’s Band of Outsiders (1964) — getting a week’s run in a lovely new print at the Music Box — it helps to know that it was made four years after François Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player and three years before Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde. Both Band of Outsiders and Shoot the Piano Player are low-budget black-and-white French thrillers adapted from American crime novels translated into French for the celebrated Serie Noire collection, and they were abject box-office flops on both sides of the Atlantic — though today they embody the glories of the French New Wave in a good many people’s minds. By contrast, Bonnie and Clyde, a Hollywood movie in color that was profoundly influenced by these two films, was a huge success, and its lyrical depictions of violence changed the direction of American cinema.

All three films are mixtures of tragedy and farce, violence and romance, with an uncertain emotional tone. When Band of Outsiders and Shoot the Piano Player were first released, audiences didn’t know what to make of this mix, but when they saw Bonnie and Clyde they were exhilarated by its ambiguities. Read more

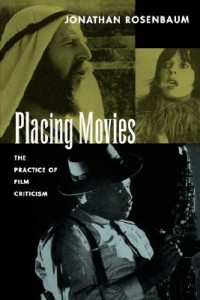

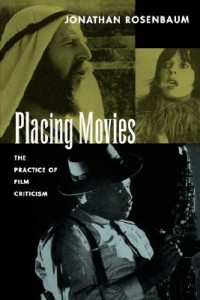

This is the Introduction to the second section of my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (University of California Press, 1993). I’ve taken the liberty of adding a few links to some of the pieces of mine mentioned here which appear on this web site. — J.R.

I should begin here with a somewhat embarrassed confession about a methodology I have employed with increasing frequency, especially since the mid-1980s — the practice of recycling certain elements from my earlier criticism. On a purely practical level, it can of course be argued that very few people who read me in, say, the Monthly Film Bulletin in 1974 are likely to be following my weekly columns in the Chicago Reader two decades later, and that my pieces for Soho News in 1980 (to cite another random example) are not likely to have survived in the periodical collections of many libraries. But I still blush to admit that, in a hatchet job I performed on Donald Richie’s book on Ozu for Sight and Sound in 1975, I sharply reproached Richie for reusing the same phrases about Ozu again and again in his own criticism. This was written at a relatively early stage in my own career when I imagined other film buffs like myself going to libraries and reading virtually everything in print on a given topic; I didn’t really think through the implications of writing about the same films and filmmakers for different audiences in separate countries over many decades — as Richie had certainly already done at that point, and as I have subsequently done. Read more

Written for Sight and Sound‘s documentary film poll in their September 2014 issue, and posted online with partial corrections (and some new errors, such as spelling James Benning’s RR “Rr”). . Two unfortunate differences between my ten-best list and the one they published on paper is (1) the exclusion (through an oversight) of my 9th selection, Peter Thompson‘s Universal Hotel/Universal Citizen (although online they now list only Universal Hotel and exclude Universal Citizen) and (2) my specification that I was referring only to the French version of Rossellini’s India — a version that I vastly prefer to the Italian version, though more as fiction than for any “documentary” reasons (which applies to most or all of my other choices). This gives an added truth to James Benning’s own bold contribution to the same poll, well worth quoting in full: “Titanic (Cameron). This is my only vote: an amazing document of bad acting. And, I might add, all films are fictions.” — J.R.

SHOAH

There are documentary filmmakers who plant their stakes within existing traditions and those for whom cinema has to be reinvented. Claude Lanzmann clearly belongs in the latter category. Of course cinema already had to exist in order to allow Lanzmann to make Shoah (1985) — named after the Hebrew word for annihilation — but he also had to rethink what cinema could be. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, November 1974, Vol. 41, No. 490. — J.R.

Portiere di Notte, Il (The Night Porter)

Italy, 1973

Director: Liliana Cavani

Cert—X. dist—Avco-Embassy. p.c—Lotar Film. A Robert Gordon

Edwards/Esa De Dimone production. A Joseph E. Levine presentation

for Ital Noleggio Cinematografico. p—Robert Gordon Edwards. p. staff—

Umberto Sambuco, Dino di Dionisio, Roberto Edwards, (Vienna) Otto

Dworak. asst. d–Franco Cirino, Paola Tallarigo, (Vienna) Johann

Freisinger. sc–Liliana Cavani, Italo Moscati. story–Liliana Cavani,

Barbara Alberti, Amedeo Pagani. ph–Alfio Contini. co1–Technicolor;

prints by Eastman Colour. col. sup–Ernesto Novelli. ed–Franco Arcalli.

a.d–Nedo Azzini, Jean-Marie Simon. set dec–Osvaldo Desideri. m/m.d—

Daniele Paris. cost–Piero Tosi. sd. ed–Michael Billingsley. sd. rec—

Fausto Ancillai. sd. re-rec–Decio Trani. post-synchronisation d–Robert

Rietty. sd. effects–Roberto Arcangeli. l.p–Dirk Bogarde (Max),

Charlotte Rampling (Lucia), Philippe Leroy (Klaus), Gabriele Ferzetti (Hans),

Giuseppe Addobbati (Stumm), Isa Miranda (Countess Stein), Nino

Bignamini (Adolph), Marino Mase’ (Atherton), Amedeo Amodia (Bert),

Piero Vida (Day Porter), Geoffrey Copleston (Kurt), Manfred Freiberger

(Dobson), Ugo Cardea (Mario), Hilda Gunther (Greta), Nora Ricci

(Neighbour), Piero Mazzinghi (Concierge), Kai S. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, October 1974 (Vol. 41, No. 489). Postscript: Thanks (once again!) to Ehsan Khoshbakht for providing me with an extra illustration for this review. — J.R.

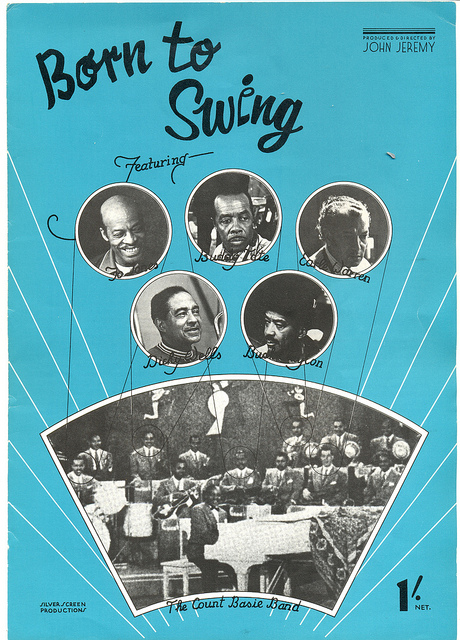

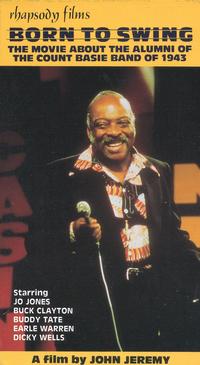

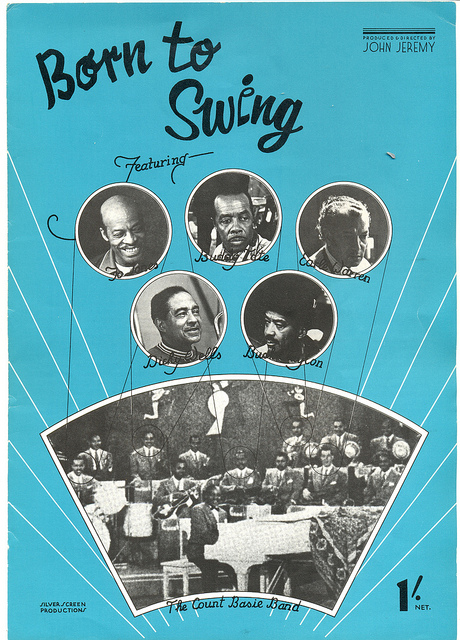

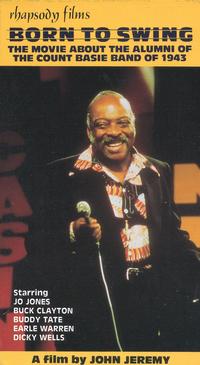

Born to Swing

Great Britain, 1973

Director: John Jeremy

Dist–TCB. p.c–Silverscreen Productions. p–John Jeremy. p. manager—

Angus Trowbridge. sc–John Jeremy. ph–Peter Davis, Tohru Nakamura.

photographs–Ernie Smith, Valerie Wilmer. ed–John Jererny. m–Buddy

Tate, Earle Warren, Joe Newman, Dicky Wells, Eddie Durham, Snub

Mosley, Gene Ramey, Tommy Flanagan, Jo Jones, The Count Basie

Band (1943). m. rec—Fred Miller. sd. rec—Ron Yoshida. sd. re-rec—

Hugh Strain. narrator–Humphrey Lyttelton. with–Buck Clayton, John

Hammond, Andy Kirk, Jo Jones, Albert McCarthy, Gene Krupa, Snub

Mosley, Joe Newman, Buddy Tate, Earle Warren, Dicky Wells. 1,773 ft.

49 mins. (16 mm.).

This engaging jazz film has both a general subject and a specific

one. Generally, it is about American swing music of the past;

specifically, its main focus is six veterans of Count Basie’s band in

the present. Interspersed with a 1943 clip of the Basie band inspiring

some athletic dancers are album covers, flurries of sheet music,

neon signs, and a string of short reminiscences: by Andy Kirk,

about his stint with the Eleven Clouds of Joy; Snub Mosley, about

New York in the Thirties; the doorman at Jimmy Ryan’s, about

52nd Street; Gene Krupa, mainly about himself. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 23, 2004). — J.R.

The Corporation

The Corporation

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Mark Achbar and Jennifer Abbott

Written by Joel Bakan, Harold Crooks, and Achbar

Narrated by Mikela J. Mikael.

A month ago I attended back-to-back press screenings of two major documentaries, Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 and The Corporation, which finally opened here last week. Though it would have broken with industry protocol to have said so at the time, before both movies had opened, it was clear that The Corporation — a 2003 Canadian film by Mark Achbar, Jennifer Abbott, and Joel Bakan — was a better film, and second looks at both movies has only confirmed this impression. Michael Moore’s movie probably startles people who rely mostly on TV for their news, but The Corporation will shock even those who keep close track of newspapers and magazines. In fact, it goes beyond shocking in obliging us to ask ourselves how far we’re all prepared to go in our defense of capitalism.

Far enough to jeopardize our health and the survival of the planet? Maybe not, but at the moment it’s corporations that appear to have the power to decide. And the stories this film uses to demonstrate that are chilling. Read more

From the February 25, 1994 Chicago Reader. It seems that a good many colleagues have ranked this film higher in Mike Leigh’s oeuvre than I did at the time; perhaps today I’d agree with them. — J.R.

*** NAKED

(A must-see)

Directed and written by Mike Leigh

With David Thewlis, Lesley Sharp, Katrin Cartlidge, Gregg Cruttwell, Claire Skinner, Peter Wight, Deborah Maclaren, and Gina McKee.

Mike Leigh’s virtuosity as a writer-director and the raw theatrical power of David Thewlis, his lead actor, combine with the sheer unpleasantness of much of Naked to make it a disturbingly ambiguous experience. The apocalyptic, end-of-the-millennium rage of Thewlis’s Johnny — an articulate, grungy working-class lout on the dole who abuses women and spews negativity — registers at times as Leigh’s commentary on the bleak harvest of Thatcherism. But at other times it registers as the ravings of a malcontent too frustrated and paralyzed to even know what he wants. Sorting out the intelligence from the hysteria is no easy matter, and the picture rubs our noses in this uncertainty so remorselessly that we sometimes forget that what we’re watching is largely a comedy.

The first glimpse we get of Johnny, he’s having some very rough sex with a nameless woman in a Manchester alley. Read more

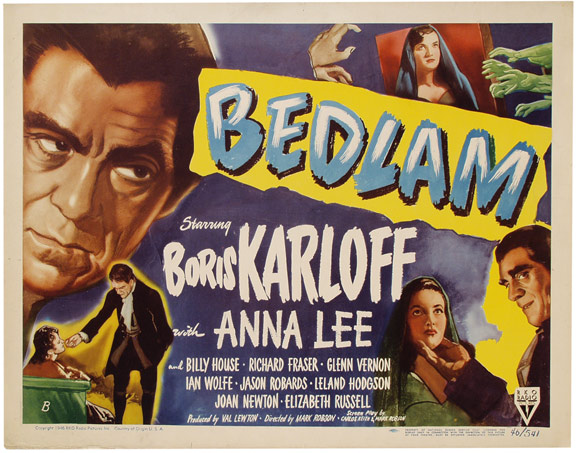

From Monthly Film Bulletin, November 1974 (Vol. 41, No. 490). — J.R.

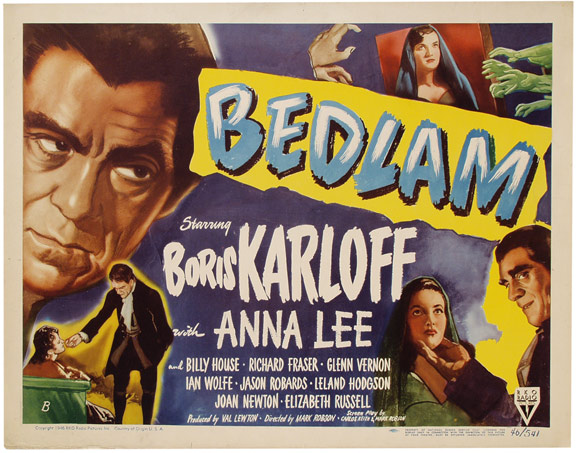

Bedlam

U.S.A., 1946 Director: Mark Robson

London, 1761. Attempting to escape from the St. Mary of Bethlehem lunatic asylum, commonly known as Bedlam, a poet named Colby is forced by Sims, the apothecary general in charge, to drop from a railing, and he falls to his death. Lord Mortimer and his ‘protégée’ Nell Bowen, passing by in a carriage, question Sims about the incident, and are assured it was an accident. After subsequently paying a visit to the asylum, Nell is appalled by the living conditions and Sims’ sadistic treatment of the inmates, and appeals to Lord Mortimer to make a charitable donation. But Sims dissuades the latter from doing so. When Nell joins forces with John Wilkes to turn the cause into a political issue, Sims contrives to have her declared insane and committed to Bedlam. Frightened for her safety — and securing a trowel from Hannay, a sympathetic Quaker brickmason, for protection — she none the less elicits the respect and loyalty of the other inmates, and when Sims locks her in a cage with a supposedly dangerous lunatic, she successfully placates her cellmate. Read more

The Corporation

The Corporation