From the Chicago Reader (March 15, 1996). — J.R.

Deseret

Directed and written byJames Benning

Narrated by Fred Gardner.

Andre Gide’s The Counterfeiters is too tremendous a thing for praises. To say of it “Here is a magnificent novel” is rather like gazing into the Grand Canyon and remarking, “Well, well, well; quite a slice.”

Doubtless you have heard that this book is not pleasant. Neither is the Atlantic Ocean. — Dorothy Parker

One of the main characteristics of experimental films is that they tend to make hash of the terms we use to speak about narrative features, and James Benning’s haunting, beautiful, and awesome Deseret (1995) — his eighth feature-length film — performs this valuable function from the outset. To say that Deseret is “directed” and “written” by Benning requires some bending of the categories. He “directed” it insofar as he conceived the project, filmed the images, recorded the sound, and edited the sound and images; he “wrote” it insofar as he compiled and edited the texts that are read offscreen by Fred Gardner, though he didn’t write them. In a Hollywood film the directorial tasks described above would be carried out by a producer, cinematographer, sound recordist, editor, and sound editor; it’s anybody’s guess what the compiler and editor of the text would be called (researcher? script editor? production assistant?).

Yet it still seems right to call Benning the writer and director of Deseret. Part of the art he shows in compiling and editing the source material for the narration — 93 news stories from the New York Times between 1852 and 1992 about what’s today known as Utah — is shaping them into a single text that qualifies as his own writing. And surely by giving a discernible, if often mysterious, direction to the images and sounds he recorded in contemporary Utah he’s entitled to be considered director as well as producer.

Broadly speaking, Deseret — whose title refers to the name the territory of Utah originally proposed for itself when campaigning for statehood in the 1860s (it joined the union as Utah in 1896) — consists of the subtle, artful, and complex interface of the condensed news stories, the recorded sounds, and several hundred stationary shots. Each shot generally corresponds to a sentence in the narration, the only exception being that each of the film’s 93 segments begins without narration; the narration of a news story always begins with the second shot, on the lower portion of which is superimposed the story’s date.

At first one might assume that Benning is simply showing us the sites today where the events being described took place, but it soon becomes apparent that he’s doing no such thing. He’s noted that each segment contains at least one shot that refers in some fashion to the news story, but how is frequently unclear; indeed, the relevance of image to text is often so tenuous that a rift between them is created — a rift each viewer is obliged to fill.

If the space of the written text is historical and the space of the audiovisual text is, broadly speaking, painterly, the space of the rift between the two is, oddly enough, novelistic — a story of Utah each viewer winds up constructing, using his or her own imagination as well as the historical and painterly elements. From this point of view the writer-director of the experience of Deseret becomes each spectator in collaboration with Benning.

A few basic facts should be set down about the New York Times stories. Grouping them by decade, over half come from the first two and last two decades: 22 from the 1850s, 9 from the 1860s, 18 from the 1980s, and 8 from the 1990s. The other decades get only 2 or 3 stories apiece, apart from the 1930s (4), the 1960s (5), and the 1970s (6). In other words, Benning has put most of his emphasis on the beginning and end of his chronology, which encourages us to note parallels between them. Forty-eight of the stories allude to Mormons, and much of the focus throughout the chronology is on violent struggle — especially skirmishes between Mormons and Indians and battles waged by Mormons and Indians against the federal government. (Echoes of the Waco massacre recur periodically.) Closer to the present, a good many stories relate to nuclear testing, biological-weapons development, and toxic-waste sites.

The obvious alienation of the New York Times reporters from both the Mormons and the Indians (as well as their relative closeness to the federal government) is central to these accounts, and this distance corresponds to Benning’s position as touristic landscape photographer. The absence of people from almost every shot in Deseret is matched by a rather dim sense of human personality in most of the news stories, which are clearly confounded by the strange behavior of alien tribes (Indians and Mormons). The Times‘s reporters represented east-coast establishment values; Benning comes from a working-class section of Milwaukee and was once involved in grass-roots leftist politics — yet his position is also that of an outsider.

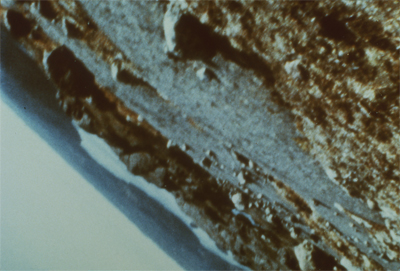

Benning has summarized his Utah landscape shots as follows: “desert, mountains, and red rock country with Anasazi petroglyphs [Indian rock carvings that clearly predate the news stories] and Mormon pioneer ruins.” This list summarizes most of what we see in the film, though it leaves out a great deal, including occasional urban landscapes, a good many churches, a couple of government buildings, one parked airplane, two waterfalls, some industrial plants and toxic dumps, quarries and cemeteries, a huge convenience store and parking lot, a filling station, a cluster of fast-food outlets, highways, a few lakes, sheep and cows (as well as a deer and a zoo elephant), Robert Smithson’s celebrated Spiral Jetty (a vast 1970 sculpture that’s accorded a news story of its own, albeit two segments later), and several signs (designating Dugwat, private property, Brigham, Deseret, a curve in the road, a safety slogan, and, in the final shot, Utah). I even recall two shots featuring people, both clearly posed: a family in a farm setting (accompanied by an 1862 story about congressional amendments to a bill prohibiting polygamy and annulling the laws of Utah on that subject) and two little girls (accompanied by a 1963 story about the effect of radioactive iodine on Utah children).

Most of these shots are beautifully and evocatively composed, in contrast to the plodding if functional prose of the news stories, though the ambient sounds that accompany the images often help us grasp them as environments rather than as mere pictures suitable for hanging. (Benning usually avoids sync sound even when sound and image seem to be matched, and I assume he’s mainly following that practice here, though at least one shot — a deer raising its head at the sound of an offscreen gunshot or backfiring car, which goes with a story about the “killing of 5,298 predatory animals with firearms and traps in 1919” and the poisoning of 11,000 to 15,000 more — suggests that he isn’t adhering to this principle consistently.)

But the rationale for the juxtaposition of the stories and the images and ambient sounds is a good deal more mysterious. In the past Benning’s taste for puns and his background in mathematics have led him to play obscure games that viewers are unlikely to catch. To cite two characteristic examples from One Way Boogie Woogie (1977), one of his best early features (along with 11 x 14, made the previous year): A shot of an American flag accompanied by a sportscaster reporting in German on a Milwaukee Brewers game and a batter named Johns alludes to Milwaukee’s ethnic background and the flag paintings of Jasper Johns. And during an extended street shot that shows a sign on top of a building detailing the history of pi, a man emerges from the building carrying a pie and almost gets run over.

I can’t say whether such games informed Benning’s editing choices in Deseret, but only a few of the shots allude to the news stories in ways that are apparent, though an abandoned storefront is seen with an 1867 story about a burglar in a saddle shop being mowed down with a double-barreled shotgun, fossil traces accompany a 1925 story about a search for dinosaur skeletons, speeding cars go with a 1937 story about a famous speedway, a filling station illustrates part of a 1976 story about the $100 million Howard Hughes willed filling-station operator Melvin Dummar, and a toxic-waste site is paired with a 1984 story about an Environmental Protection Agency report. But unless I missed something, it’s anyone’s guess what the connection is between shot and text when we hear an 1855 story about a prominent Salt Lake City citizen espousing the continuance of slavery, an 1885 story about the refusal of most Utah citizens to celebrate the Fourth of July, and a 1944 story about the building of a concentration camp for Japanese-Americans, described as the fifth largest city in Utah.

But whether or not one can spot links between places and texts, the viewer is still compelled to construct a Utah and a history of his or her own — a makeshift novel or at least fragments of such a novel — in which all these elements belong. In this respect Deseret differs profoundly from Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet’s Too Early, Too Late (1981), perhaps the greatest of all landscape films, where the French and Egyptian locations shown are always precisely keyed to the sites mentioned in the two political texts being read offscreen. It differs even more profoundly from Michael Snow’s 190-minute La région centrale (1971), my candidate for the second greatest landscape film — continuous 360-degree pans (combined with some zooms) across a spectacular remote mountain vista in Quebec — which has no political or social dimension of any kind (even the cinematographer was factored out of Snow’s preprogrammed technology).

Neither apolitical like Snow nor Marxist like Straub-Huillet, Benning stands somewhere in between these two extremes. He solicits the spectator’s active collaboration, as Straub-Huillet and Snow do in their separate fashions, but he also gives the spectator a much wider range of materials to work with — a database known variously as Deseret and Utah that’s neither as materialist as Straub-Huillet’s French and Egyptian countrysides nor as abstract as Snow’s Quebecois mountain range.

I’ve seen Deseret twice, each time in a cold auditorium on a winter morning: last month at the Rotterdam film festival, with Benning in attendance, and last week at Chicago Filmmakers, where Deseret is also showing this Friday at 8 PM, again with Benning in attendance. The film was also shown in the morning at the Sundance festival in January. One reason I’m bringing up winter is that much of Deseret appears to have been shot at that time of year, making it an appropriate time of year to see it. And one reason I’m mentioning morning is that at festivals nowadays — even festivals of independent films like Sundance or Rotterdam — selections like Deseret aren’t mainstream enough to get evening slots. So count yourself lucky that Chicago Filmmakers is presenting it at prime time.

What kind of space is Deseret allowed to have in this country? In a market-driven culture where all films are expected to belong to genres — even if they turn out to be unwieldy categories that exclude as much as they include, such as “experimental film” and “art film” — hardly any at all. For most of his career, it seems, Benning has shown his films mainly in art museums, which often means that the audience sits on folding chairs or benches; given the fine-arts aspect of this work, this seems logical enough, but the links between his work and other kinds of movies tend to get obscured by this arrangement.

Placing Deseret in the “experimental” category automatically suggests more kinship with the works of Maya Deren, Stan Brakhage, and Peter Kubelka than with those of Chantal Akerman, Terrence Malick, or Gus Van Sant. If the latter group can be said to belong more to the history of landscape art than the former, that’s clearly where Benning belongs. Yet as a filmmaker who started out painting, drawing, and studying mathematics in graduate school, he also has a strong relationship to structural filmmakers such as Snow and Hollis Frampton, whose works are often preoccupied with time, duration, and history and are also shown mainly in art museums and spaces like Chicago Filmmakers’s Kino-Eye Cinema.

In a more enlightened culture Benning’s uncanny flair for framing landscapes could be set alongside the compositional gifts of Steven Spielberg, even though Spielberg’s painterly eye would come in second. In the utopia I have in mind literary critics would be more concerned with the fictional narrative spaces opened up by Benning’s films than with the fictional narrative spaces closed down by, say, Ang Lee and Emma Thompson’s (as opposed to Jane Austen’s) Sense and Sensibility. After all, the topographical and historical spaces opened up by Benning — and the fictional and narrative spaces created by every viewer in relation to them — allow for genuine reconnaissance missions. By contrast, Lee and Thompson’s topographical and historical spaces are at best pared-down illustrations of — and touristic theme-park rides through — territories conclusively mapped out by Austen 200 years ago.

To get a proper sense of all it’s doing and setting in motion, Deseret should probably be considered in relation to Norman Mailer’s best novel, The Executioner’s Song — a narrative about Utah and Mormons and violence and the potential emptiness in all three — as well as other experimental films like Too Early, Too Late, La région centrale, and Frampton’s Zorns Lemma and Nostalgia (neither of which is much concerned with landscape, but both of which have serial constructions that suggest Deseret). Ideally, such a film should be seen and discussed not only by film critics but by historians and people concerned with literature and the fine arts, because it’s saying things about aspects of American culture that in the mainstream only corny, simpleminded demagogues like Oliver Stone are being allowed to hold forth on. Benning has much more to say about the vastness, complexity, and terror of American life than Stone (or Ron Howard, for that matter) has ever dreamed of. But because he’s saying it in cold auditoriums, in 16-millimeter — without even the “benefit” of preview copies on video — and without big-studio approval, most of our tastemakers who adhere to the cultural agenda set by banks aren’t even going to think of listening.