From the Chicago Reader (June 2, 1989). — J.R.

INDIANA JONES AND THE LAST CRUSADE * (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Steven Spielberg

Written by Jeffrey Boam, George Lucas, and Menno Meyjes

With Harrison Ford, Sean Connery, River Phoenix, Denholm Elliott, Alison Doody,

Julian Glover, and John Rhys-Davies.

Nazis are fun! Jesus is fun! Arthurian legends are fun! Third world countries are fun! Caves are fun! The Holy Grail is fun! Lots of snakes and rats and skeletons are fun! Chases are fun! Narrow escapes are fun! Explosions are fun! Indiana Jones is fun! Indiana Jones’s father is fun!

Put them all together and you get the third panel in Steven Spielberg and George Lucas’s Indiana Jones triptych — more fun than a barrel of monkeys (or Nazis, chalices, snakes, rats, skeletons — whatever). Though Hitler, Jesus, women, the third world, and, by implication, most of the rest of civilization ultimately take a backseat to the uneasy yet affectionate relationship between a grown boy and his dad — and all those millions of people exterminated by the Nazis (for instance) don’t even warrant so much as a look-in — this is nothing new in the Lucas-Spielberg canon; it isn’t even anything new in movies. It’s a standard psychoanalytical truism that whatever is most actively repressed in a work of art will nonetheless be legible to a trained eye.

The macabre triumph of Lucas-Spielberg is how legible what they are repressing is to an untrained eye. The trick is to reduce everything to campy derisiveness, so that not even the father-son relationship, which is supposed to matter, is treated as if it mattered: the movie makes it as much of a joke as Hitler, who pops up simply so that Indy can inadvertently collect his autograph.

Raiders of the Lost Ark, the first Indiana Jones picture, is set in 1936, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom in 1935. The new movie begins in 1912, when Indy (River Phoenix) is a Boy Scout, then flashes ahead to 1938, when he’s an adventurer (Harrison Ford) slugging it out with villains off the Portuguese coast. In the prologue — which explains how Indy acquired his felt hat, his fear of snakes, his facial scar, and his taste for bullwhips — he comes upon a group of men who have just unearthed a 16th-century relic in a cave in Utah; feeling morally outraged (“This belongs in a museum”), Indy makes off with the gold cross himself, leading to a chase that culminates on a moving circus train.

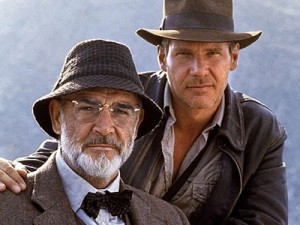

This is a somewhat more vulnerable and disillusioned Indy than we’ve encountered before. Racing home to turn the cross over to his medievalist father (Sean Connery), he encounters only frustration: first a lack of interest from his dad, then a visit from both his pursuers and the sheriff, who retrieve the cross and hand it over to a gentleman in white. Twenty-six years later, Indy’s fighting aboard a sinking ship, attempting to reclaim the same cross from the same gentleman (miraculously dressed — for purposes of easy identification — in the same cream-colored suit). When he repeats his corny motive — “That belongs in a museum” — his adversary replies, “So do you!” The implications of this are somewhat akin to Clint Eastwood having Dirty Harry sound off against the public’s taste for violence in The Dead Pool; Lucas and Spielberg are trying to distance themselves from their own hero, even though in this case as in Eastwood’s it’s a clear case of the pot calling the kettle black.

The story proper (which I intend to give away pretty much of, so let this be fair warning) begins only after Indy is back in his Clark Kent mode, working as an archaeology professor in New York. He is summoned by the wealthy Walter Donovan (Julian Glover), who shows him a stone tablet that describes the final resting place of the Holy Grail, the chalice used by Jesus at the Last Supper. It soon emerges that Indy’s father — a religious believer unlike his son — has already left for Europe in search of the Grail and disappeared. But he’s mailed his journal, packed with clues, back to Indy, who promptly flies to Venice in search of both the Grail and his father. Indy is greeted in Venice by Dr. Elsa Schneider (Alison Doody), an apparent ally who, along with Donovan, proves to be working for the Nazis to recover the Grail for profane purposes (“eternal life”).

After Indy becomes romantically and sexually involved with Elsa (while still believing her an ally), he finds his father being held prisoner by the Nazis in a castle, and learns that the old man has already slept with her himself. (Thereafter, Elsa remains a Nazi villain with occasional “good” impulses; the only genuine romantic interest that remains is between father and son.) When the Holy Grail is finally found, after many tests and obstacles, in a mythical third world country, it proves to be every bit as “magical” as the Ark of the Covenant and the Sankara stones from the first two Indiana Jones movies, resurrecting Indy’s father after he’s shot in the gut, dispatching all the villains, inculcating Indy with religious faith, and even improving his relationship with his dad.

I can understand why the creators of this movie didn’t want to spoil our fun by reminding us of what drove us into the theater in the first place. The fact that they can transport us with fantasy while making full use of the iconic residue left by Jesus, Hitler and the Nazis, and a few other “entertainment” standbys from the real world is what I find so creepy. A genuine if troubled believer like Martin Scorsese gets the religious world in an uproar for daring to express himself in The Last Temptation of Christ, but a work of cynical expediency like Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, which uses Christianity the way Russ Meyer uses large breasts, is all set to be received like a secular sacrament. It could be argued that Scorsese’s film has artistic ambitions and pretensions while Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade pretends to nothing more than light entertainment. This is superficially true — but only up to a point considering the cultural importance being accorded to this light entertainment, which is currently showing on 2,327 screens in North America and which racked up $50 million in ticket sales on its first day.

I have fond memories of action serials from my grammar school days. (Superman, Batman, Mysterious Island, and Captain Video are the first titles that come to mind.) Insofar as the Star Wars and Indiana Jones cycles both have their origins in Hollywood serials, it would be comforting to think that these cycles are nothing more than their contemporary equivalents, with the same cavalier uses of stock villains, icons, and naive attitudes. Comforting, but wrong. Consider a few of the more significant differences:

(1) Serials were interactive. One spent a whole week debating with friends how Superman or Captain Video would survive his apparent destruction in the most recent episode, and if the solutions proposed were often better than what the serials themselves furnished, this effectively created new narratives in the minds of the spectators, each one nurtured over several days. The entertainment machines of Lucas-Spielberg, by contrast, are so dictatorial that they tend to stifle creative input; far from giving us time to ponder, the breathless pacing denies us the luxury of even a few seconds of thought.

(2) It would be safe to say that by and large, these serials were ideologically innocent; if Flash Gordon‘s Ming the Merciless represents a racist stereotype, the “Yellow Peril” of the 30s, you can bet this wasn’t cause for much deliberation at script conferences. Unlike George Lucas, who in recent years has taken to propounding the work of myth scholars like Joseph Campbell, the makers of these serials were basically interested in spinning yarns, without much help from Freud or Jung or academic critics (some of whom, like Frank McConnell, have responded by writing about Star Wars as if it were right up there with the works of Homer, Virgil, and Dante).

(3) Finally, and most important, serials were virtually ignored by mainstream culture; like comic books, they were cheaply produced and regarded as worthless and inconsequential by most adults; and you certainly wouldn’t find major newsmagazines devoting three-page spreads to them. If “good clean fun” was all they represented, it seems somehow disproportionate to claim the same for the Indiana Jones cycle, which descends on our lives with all the effervescence of a ten-ton elephant.

To get to the bottom of this — or at least the beginning — one has to go back not to Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), but to Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977), Spielberg’s and Lucas’s first megahits, respectively, which have proved to be the loci classici for their separate but overlapping careers and visions. It was Jaws that introduced us to Spielberg’s mastery of Hitchcockian point-of-view shots and John Williams’s portentous, thumping music, both integral parts of the audience’s Pavlovian instructions. There is also a marginalization of women (except as hausfrau or shark bait) that permits the boys to get together and take care of business, the related suggestion of vagina dentata (in this case, the shark) as the ultimate horror, and the square middle-class hero who takes the world on his shoulders and eventually delivers the goods. (Plain cop Roy Scheider defeats the shark rather than working-class adventurer Robert Shaw or upper-class hippie intellectual Richard Dreyfuss.)

Most subtle of all was the adroit handling of the audience’s ideological biases. Jaws was made during Watergate, and the corruptness of the town mayor was milked for every possible effect without ever making this contemporary undertone overt; audiences were made to feel morally outraged by this character’s behavior without for an instant connecting it to any real-life politicians — if only because they never had an instant to entertain any independent thought.

None of this, of course, had anything to do with movie serials, apart from a capacity to hold audiences at the edges of their seats. But two years later came Lucas’s Star Wars, perhaps the first fully postmodernist movie hit, which pillaged everything from Flash Gordon to The Searchers to Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda (with healthy doses of Disney, De Mille, Arthurian legends, and Hollywood World War II epics) to stock its storyboards, and which, while following the overall narrative drift of a Saturday serial, utilized fragmented editing in such a way that it made Jaws seem leisurely by comparison. If Spielberg’s major reference point was Hitchcock, and if the experiences he provoked were more or less communal (the thrill of a collective adventure), Lucas’s nearest equivalents were pinball machines and arcade shooting games, and the experiences he provoked were relatively solitary and narcissistic ecstasies of annihilation.

Four years later, when Spielberg and Lucas pooled their talents to make Raiders of the Lost Ark, Lucas’s vision ultimately had the upper hand, with Spielberg filling out and illustrating the postmodern combos (such as the fabled Ark of the Covenant from the 1951 Hollywood epic David and Bathsheba combined with the Great Whatsit from Kiss Me Deadly — nuclear death in Pandora’s Box — and the flashy Mount Sinai effects from De Mille’s Ten Commandments). Where the two artificers really came together was in the concentration of all their heavy artillery on a single effect and theme: movies as the only reality — a universe in which God becomes just another hotshot movie director. Thanks to this happy collusion, the communal shrieks, oohs, and ahs elicited by Spielberg could blend with the masturbatory sexual releases provided by Lucas to yield a single pseudoreligious experience — ecstasies of annihilation forming the grace notes in a collective adventure, with little pockets of equally telegraphed Spielbergian sobs and Lucasian smirks tucked away in the various crevices.

To be fair about it, all three of the Indiana Jones movies are streamlined, fast-moving entertainments, and with each of them centered around a separate world religion — Judaism in Raiders, Hinduism in The Temple of Doom, and Christianity in the latest one — their compound resonance is a bit like a Disney-style theme park. Each section of this park is presided over by a separate vengeful and inscrutable (two-headed) deity — not gods recognizable from any of the holy books, but fantastic creations of the moviemakers who reduce deity to special effects. The awe evoked by the parting of the Red Sea in The Ten Commandments may have been partially kitsch-inspired, but elements of genuine reverence still played a part in the overall experience.

The awe evoked by God’s miracles in the Indiana Jones movies, by contrast, is strictly technological — awe produced by equipment not transcendence. (In his efforts to get to the Holy Grail Indy has to face numerous challenges, which include playing hopscotch on the letters that spell out “Jehovah” and making a “leap of faith” across an abyss. The latter feat recalls the moment in Peter Pan, a long-planned Spielberg project, when an audience is asked collectively to believe in fairies in order to save the life of Tinkerbell.)

Just as Jaws was grounded in Watergate, the Indiana Jones trilogy can be read in reference to Reagan and Reaganism. In his book A Cinema of Loneliness, Robert Phillip Kolker has written persuasively about a key moment in Raiders of the Lost Ark, the moment that invariably elicited the loudest laughter and cheers, when Indy comes face to face with a giant bearded and turbaned Arab who’s grinning and brandishing a large saber. After an ambiguous pause, Indy simply takes out his gun, with an exasperated and contemptuous expression, and shoots him. As Kolker points out, “The ideological positioning of the spectator is made quite certain. Subjected to imagined humiliations at the hands of Middle Easterners — figures so outside known cultural limits that they have only just barely achieved the rank of stereotype — the audience, having given itself over to the hero, finds it can now subject the villain to instant, guiltless retribution. . . . Reaganism had its first explicit filmic representation.”

In Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Reaganism figures in the notion of Indy as the paternal savior of the third world, as he virtually adopts a Chinese orphan (named Short Round, after the Korean orphan in Samuel Fuller’s The Steel Helmet), and recovers the Sankara stones in order to save an Indian village from famine and misery. Apparently taking to heart some of the charges of racism and imperialism in the first two Indiana Jones movies, Lucas and Spielberg have toned down the contemptuous treatment of the third world without actually eliminating it. (How could the Indiana Jones cycle begin to exist without such attitudes?) But as if to compensate for this absence, they have installed the presence and legacy of Reagan even more integrally in their overall conception, in the figure of Indy’s father — a character whose age, wistful vagueness, old-fashioned habits, religious faith, and neglectfulness toward his son seem to sum up the public’s ambivalent memories of its retired monarch. This is a character, after all, who insists on calling his son “Junior” (in spite of Indy’s repeated protests), who slaps him at one point for “blaspheming,” and who remarks, when he and Indy sneak into a Nazi book-burning, “Boy, we’re pilgrims in an unholy land.”

Given the third world subtext and setting of the last portion of the film, it would be right in character for him to start talking about Armageddon, too. In his presence, Indy often reverts to the manner of an awkward and petulant teenager, sulking and complaining and yearning desperately for the validation and recognition that the old man never quite dishes out. The film represents this as a kind of unrequited romance; Elsa, in keeping with the strictly “functional” nature of the females throughout the cycle, is important mainly because she provides the connecting tubes between Senior and Junior.

Another distinguishing characteristic of this little boy’s world is the nature of its enclosures. There’s a preponderance of caves in all three of the Indiana Jones movies; The Last Crusade begins and ends with a cave, and even finds room for a third one at a crucial juncture in Venice. (One of these is called a catacomb, and another looks like a temple, but they’re all essentially the same place.) Without dwelling too much on the Freudian implications of this — except to note that they recall the vagina dentata motif of Jaws — it’s worth remarking that the major filmmaker obsessed with caves, Fritz Lang, generally used them as the repositories of repressed social secrets, not as the arsenals for divine artillery. From the lair of the petrified dwarfs in Siegfried and the workers’ city in Metropolis to the numerous caves in The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Hindu Tomb (hiding place, dungeon, underground temple, lepers’ colony) — not to mention the basements in M and the Dr. Mabuse films — these Langian enclosures always suggest society’s dark underside.

In the more infantile, presocial Indiana Jones cycle, caves are strictly fun houses that suggest the overstuffed closets of millionaires who fancy themselves as deities. The real star of the series isn’t Harrison Ford as Indiana Jones; it’s Lucas and Spielberg as the unseen Jewish God, the Hindu God, and finally Jesus Christ himself, cheerfully doling out power and life and death and love and salvation in campy doses for millions of grateful disciples.