From The Soho News (May 20-26, 1981). I’m sorry that I still haven’t managed to see Vermont in 3 1/2 Minutes, a 1963 film made by a childhood friend of mine — and that I haven’t been able to find any more illustrations for the small-gauge films that I wrote about here….My expressed feeling of solidarity with Squeeze Play was no doubt inflected by the fact that I was living in Hoboken at the time. — J.R.

May 8: At Anthology Film Archives, to see a program in “Home Made Movies: 20 Years of American 8mm and Super-8 Films” — an intriguing and varied series selected by Jim Hoberman that runs through the end of next month, warmly recommended to everyone without money who nurtures fantasies about taking over the media. I learn straight away that Linda Talbot’s Vermont in 3 1/2 Minutes is being replaced by Bear and Jane Brakhage’s Peter’s Dream, a title glossed by Jonas Mekas as referring to Peter Kubelka.

This reminds me of a somewhat troubled notion that first reared its inglorious head when I had the occasion to view all the films in the Whitney’s previous Biennial. The idea is simply that a surprising number of North American avant-garde films seem to center on the same general obsession as The Deer Hunter or Manhattan — namely, a boastful inventory of male possessions: This is my hometown, my house, my rifle, my dog, my Bolex, my woman, my art.

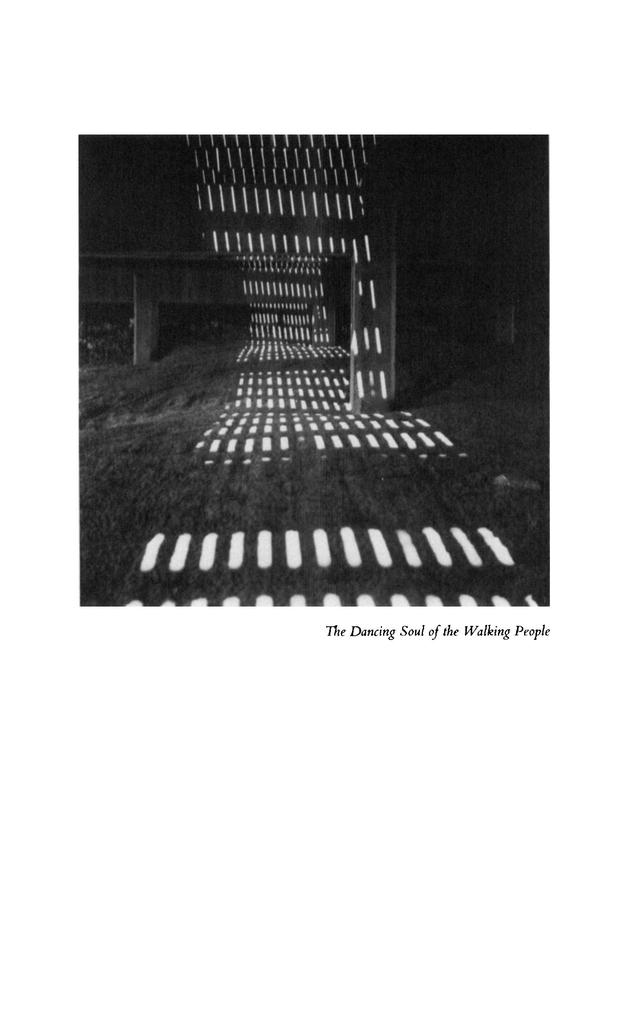

In the case of Peter’s Dream, all I actually see (which is plenty for me) is a dog and a deer playing together -– very agreeable color footage about what appear to be no one’s possessions, which leads me to regard the title as a not-very-useful encumbrance between me and the movie, however useful it might be for certain others. And when it comes to the main attraction, Paula Gladstone’s mainly black-and-white, hour-long The Dancing Soul of the Walking People, possession and dispossession both happily become very much beside the point.

Shot over a two-year period, 1974-76, in super-8, each time the filmmaker went home to Coney Island (“I’d take my camera out and walk from one end of the land to the other,” she reports in Camera Obscura No. 6;“I’d talk to people on the streets and film them.”) The Dancing Soul of the Walking People is basically concerned with the space underneath a boardwalk, a little but like the insides of a translucent zebra on a sunny day – an interesting kind of space, at once public and private, that is traversed by receding stripes of light, camera pans, and people, in fairly continuous processions and/or rhythmic patterns.

Playing against these traversals is the repeated sound of galloping hoofs, some lyrical jazz arrangements (Duke Ellington with a scat singer, George Russell, Anthony Braxton, Stravinsky’s Firebird rearranged by Alice Coltrane), “Under the Boardwalk” by The Drifters, conversation about Coney Island, and some funky black and male-oriented poetry, written a d read by Gladstone – more material, in short, that’s merely passing through.

Unfortunately, due the film’s being wound on a single reel, the music seems to undergo a kind of slow-motion distortion that seems comparable to the slightly dreamlike, underwater crawl of the images –- a funny effect when, say, harp glissandos on the soundtrack seem to go with the mottled stripes. But the kind of visual taffy-pull drift that characterizes most of the film can turn into a kind of ecstatic contemplation when it focuses on two little boys tossing up clouds of sand – magical emanations that are partially separated by jump cuts. It’s nice to see how Gladstone, like those kids, can be structural and nonpossessive at the same time.

May 10: At Loew’s Astor Plaza, I go to see Squeeze Play, a low-key, likable, dumb softcore farce that places its economic cards and cultural alliances right on the table in the opening shot. We start off with a broad view of the Manhattan skyline. “There are 10,000 stories in the big city,” intone the brooding announcer. “This isn’t one of them,” he adds –and the camera pans abruptly across the Hudson to where it’s actually stationed, in New Jersey.

Usually offering about one good-natured, witless gag per shot (“Djever hear about the rabbi who went to a monastery and became a shmonk?”) while concerning itself with a group of women forming a softball team of their own To Get Back at the Guys, Squeeze Play isn’t so very far from an entry in the English Carry On series. It’s the kind of sub-Animal-House romp where a detective has a steel-plated jockstrap (to protect him from pugnacious females), a little girl advises her big sister, “Let your tits do the talkin’, Sis,” and there’s a cut from some offscreen fellatio to an onscreen dairy custard dispenser at work.

The relaxing thing about the friendly, unassuming anonymity of a movie like Squeeze Play is that you don’t really care two beans about whether it’s “good” or not. It’s a vacation from the world of winners and losers, and the energetic cast of nobodies seems to know that, too. Nobody has to be anything “special”. “Our movies are not the sort of things critics can go out and discover,” coproducer and director of photography Lloyd Kaufman said to a New York Times business reporter last month, after showing this Jersey-made Troma production all around the U.S. for a year and a half. (New York is the last stop these days for a lot more than European art movies.) “They’re not about people discussing Vietnam,” he added. So saying that I enjoyed Squeeze Play might sound like a breach of profession, but there it is.

***

I head downtown for another program in Hoberman’s Home Movie show at Anthology. Here the question of possession gets posed again, a bit differently, by Manuel De Landa’s super-8, eight-minute color and silent Ismism (1977-79), which – as De Landa explained when I saw this film last, at the Collective – documents part of his graffiti-making activity in Manhattan. Most of this is the assembly via montage of verbal messages spread out cryptically and sequentially across the city, a word or phrase at a time, e.g., “USE/ILLEGAL/SURFACES/FOR/YOUR/ART’ and “LET THE SLANG/OF YOUR DRIVES/DRIVE LANGUAGE CRAZY.” The rest links the surreal disfigurements of diverse street posters advertising cigarettes (e.g., fleshy lips drawn over the eyes of the models). In both cases, the linkages of the film itself create a certain knowledge that’s the exclusive possession of people watching the film -– a hidden unity denied to mere pedestrians.

This brings me to the nub of a contradiction about the avant-garde: that the experience it offers is commonly one of dispossession – what the Russian formalists call “making strange,” and Jacques Rivette describes as a plunge into horror, like discovering the death of someone one has loved – while the situation most often affording this experience is one of inside knowledge, which suggests precisely the reverse in social terms (i.e., the possession of art that comes from being initiated).

This is the problem that ultimately grounds me when it comes to other filmmakers in this program –- Ericka Beckman’s very Landowish super-8 White Man Has Clean Hands (1977) and a set of 8mm Landow shorts made between 1962 and 1965. Films that are as contextual in their own terms as most of network television – and consumable, unlike De Landa’s films, only after one has absorbed their titles and/or catalogue descriptions – they can’t belong to the casual viewer (me, in this case), even when they achieve the relatively direct address of Landow’s Not a Case of Lateral Displacement (1964), which focuses on an open skin infection. (“This is my wound.”)

***

May 11: A press show of Outland – a serviceable English sci-fi spectacular, written and directed by Peter Hyams, which pits good cop Sean Connery against mercenary racketeer Peter Boyle in an ore-mining station on Jupiter. The handsomely designed Panavision look of this movie — from planet and satellites to surface landings to sexy machines to a milky-white disco bar lit from below – derives mainly from Kubrick, and helps to compensate for the even more derivative plot and dialogue, which stems basically from hunger (and a few action warhorses like High Noon by way of Dirty Harry).

The basic idea of Outland -– if you can call it an idea –- is that a cop on assignment at the stinko Con-Am compound on Jupiter learns, with the aid of a cranky female doctor named Lazarus (Frances Sternhagen), that a lot of workers have been going crazy because they’ve been given lethal amphetamines that make them work more before they flip out. Actually, this qualifies mainly as framework; the real meat of the movie is industrial design –- like the workers’ meshed-in dorm berths, which resemble the set of the Living Theater’s production of Frankenstein –- and fancy technology, both of which stake a bigger claim on one’s attention and interest than any of the people.

“Such a lot of smart equipment here, and a wreck like me to run it,” Sternhagen notes apologetically and ruefully at one point; and one wonders, indeed, who got paid more, the actress or the set designer. There’s also a virtual cameo by Kika Markham –- a plucky, beautiful actress who might be recalled from Truffaut’s Two English Girls and Rivette’s Noroît –- as Connery’s wife, who decides to split from Jupiter with their son in the first reel, and appears thereafter only in televised messages – thereby assigning more romantic interest to the spiffy message transmitter and receiver, which lands a juicier part.

***

May 12: A press show for “Filmworks ’81,” six programs of independent films selected by Regina Cornwall for presentation at The Kitchen on May 21, 22, and 23. Tom Brener’s Pilotone Study I (1976) – to be shown at 8 on the 21st with Tim Burns’ Australian underground feature Against the Grain, which I already reviewed (unfavorably) in these pages three months ago — is a lovely 12-minute study of a rural autumn landscape, no heavy ideas but some great russet tones.

Spaced out in quasi-structural terms between stationary and moving medium and long shots within each segment, with a beep sounding over each splice, the film proceeds from leaves (raking, burning) to highway (with passing cars) to the dance of a friendly dog behind a fence in relation to the unseen photographer — eventually winding up with some more raking and burning of leaves, at night, the sky modulating between lavender and orange behind silhouetted trees. So far as I can see, no possessions anywhere.

Lisa Gottlieb’s Murder in a Mist (May 22 at 8, with films by Amy Taubin and Karyn Kay) is a half-hour of well-crafted low-budget fun — a black-and-white film noir shot last year, with every last lurid detail and period effect of the genre lovingly spelled out. (The setting is 1952, Chicago.) Its only real twist is that its Chandleresque detective is a tough blonde, Meg Hammer (Joyce Hazzard), who relishes hardboiled quips like, “Relax, Sylvia, you can’t eat the Venetian blinds” and, addressing all the bad guys she’s holding up, “All of you take out your peckers and hold them tight.”

The plot of Murder in a Mist (script by Gottlieb from a Henry Beard story)is about a heroin ring that gets novices hooked via a female hygiene spray — a much better idea than anything dreamed up for Outland. Fabulous 16mm photography by Jeff Juir, in dingy places that are gorgeously lit. In contrast with the Brener movie, this is about nothing but possessions, done in the manner of a resume, with an eye clearly aimed straight at Hollywood — but, paradoxically, I like it, too. It’s make a perfect short to go with Gloria.

Tim Bruce’s 26-minute Corrigan, Having Recovered (1979) (May 21 at 8, with Adam Brooks’ Ghost Sisters) reminds me of various 16mm English art school student films I’ve seen – neat, programmatic, intelligent, interesting, a little dull. More structural ideas, based here on intersecting narratives (including a modernist music rehearsal) and adjacent spaces.

Regarding two punky (as opposed to punk) super-8 features – Betty Sussler’s Menage (to be shown at 10:15 on the 21st) and Adam Brooks’ Ghost Sisters (see above) – I can only note with fairness that they came at the end ofan afternoon devoted to enjoying the previous films, which tended to reduce my tolerance for anything else. The camera work on the latter film (some of it by none other than Jonathan Demme) is very graceful, the choice of T-shirts extremely unwitty, the soundtrack sufficiently muffled to suggest a ghost of a movie – say, a very low-energy Celine and Julie Go Boating, which is really a contradiction in terms.

Due to projection problems and fatigue, I see only the first half of Menage — a creepy film about a real-life English couple who went on a torture and killing spree with random victims in the 60s, armed with proto-Nazi visions. Most blood-curdling of all is the disturbing effect created by keeping all the violence and gore off-screen, although the sounds of people being tortured (or imitations of such) on tape are dwelt upon at length. The dialogue – much of it off-screen or out of sync – is deliberately stagy, in the manner of Straub and Huillet. Proceed at your own risk; personally, I felt evicted.

![]()