These are expanded Chicago Reader capsules written for a 2003 collection edited by Steven Jay Schneider. I contributed 72 of these in all; here are the fifth dozen, in alphabetical order. — J.R.

The Red and the White

This 1967 feature was one of the first by Hungarian filmmaker Miklós Jancsó to have some impact in the U.S., and the stylistic virtuosity, ritualistic power, and sheer beauty of his work are already fully apparent. In this black-and-white pageant, set during the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, the reds are the revolutionaries and the whites are the government forces ordered to crush them. Working in elaborately choreographed long takes with often spectacular vistas, Jancso invites us to study the mechanisms of power almost abstractly (as suggested by the Stendhalian ring of his title), with a cold eroticism that may glancingly suggest some of the subsequent work of Stanley Kubrick. But this shouldn’t mislead one into concluding that Jancsó is any way detached from either politics or emotions.

For one thing, the markedly nationalistic elements in The Red and the White could be —- and were —-interpreted as anti-Russian, especially if one considers that the film was made less than a decade after the Soviet repression of the Hungarian revolution, which left over 7,000 Hungarians dead. And significantly, although the film was a Hungarian-Russian coproduction, the Russian authorities refused to show the film in the Soviet Union.

It’s also pertinent that Jancsó’s preference for long shots can’t be translated into any sort of disdain for his actors. József Madaras, one of Jancsó’s regular actors, has explained that “With him, the actor’s face plays a subordinate role: he will formulate and express the psyche through the movements of human masses. That’s what audiences, accustomed to conventional representations, may find strange. But he insists on fully creative collaboration from his actors —- only in a manner departing from the conventional….He’ll never psychologize, never analyze. He makes you move. And from the way he keeps you moving I can figure out what he wants me to do, how he visualizes a character. He thinks in terms of music and sees in terms of rhythm.”

If you’ve never encountered Jancsó’s work, this is an ideal place to start; it was the first of his features that I saw, and it led me to many more. He may well be the key Hungarian filmmaker of the sound era, and certain later figures such as Béla Tarr would be inconceivable without him.

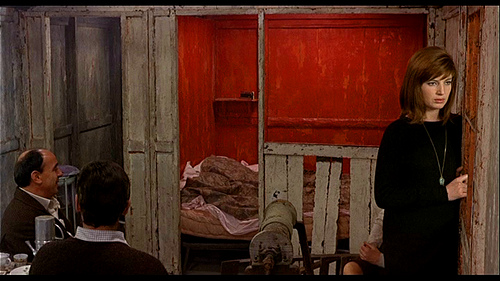

Red Desert

Michelangelo Antonioni’s first feature in color remains a high-water mark for using colors creatively, expressionistically, and beautifully; to get the precise hues he wanted, Antonioni had entire fields painted. Restored prints make it clear why audiences were so excited by his innovations, which include not only expressive use of color for moods and subtle thematic coding, but striking editing as well. The film comes at the tail end of Antonioni’s most fertile period, immediately after his remarkable trilogy consisting of L’avventura, La notte, and Eclipse. Red Desert may not be quite as good as the first and last of these, but the ecological concerns of this film look a lot more prescient today than they did in 1964. Monica Vitti plays a neurotic married woman who’s briefly attracted to industrialist Richard Harris, and Antonioni does eerie, memorable work with the industrial shapes and colors that surround her, which are shown alternately as threatening and beautiful; she walks through a science fiction landscape spotted with structures that are both disorienting and full of possibilities. Like any self-respecting Antonioni heroine, she’s looking for love and meaning — more specifically, for ways of adjusting to new forms of life — and mainly finding sex. There’s one sequence in which postcoital melancholy is strikingly conveyed via Antonioni’s color expressionism, which tends to follow the heroine’s shifting moods throughout. (“The drama is no longer psychological, but plastic,” Jean-Luc Godard suggested to the director while interviewing him about the film, to which Antonioni aptly replied, “It’s the same thing.” In the same interview, he stressed that the film was in some ways an appreciation of industrial landscapes and not simply a despairing critique, as many commentators supposed.)

The film’s most spellbinding sequence depicts a pantheistic, utopian fantasy of innocence, which the heroine recounts to her ailing son. Suggestively yet mysteriously, it implicitly offers a beautiful girl and a beautiful sea as an alternative to the troubled woman and the industrial red desert of the title.

Secrets & Lies

Mike Leigh’s gripping, multifaceted 142-minute comedy-drama, winner of the grand prize at Cannes in 1996, may well be his most accessible and optimistic picture, which helps to explain why it possibly remains the best-known work of a writer-director for stage and screen who is often best known for his anger and his merciless skewering of class differences in Thatcherite and post-Thatcher England. In this film, a young black optometrist (Marianne Jean-Baptiste) seeks out her white biological mother (Brenda Blethyn), a factory worker who put her up for adoption at birth, and as the two become acquainted, tensions build between the mother and another illegitimate daughter, between the mother and her kid brother (Timothy Spall), and between him and his wife, leading to a ferocious climax.

The dense, Ibsen-like plotting of family revelations is dramatically satisfying in broad terms, though it leaves a few details unaccounted for. But the acting is so strong — with Spall a particular standout — that you’re carried along as if by a tidal wave. The younger daughter, a close cousin of the bulimic daughter in Leigh’s earlier Life Is Sweet, is the weakest link in the chain of family discord, yet Leigh orchestrates the whole thing with such panache that you’re not likely to mind her too much.

Shadows of our Forgotten Ancestors

Adapted from a novel by Ukrainian writer M. Kotsyubinsky, Sergei Paradjanov’s extraordinary merging of myth, history, poetry, ethnography, dance, and ritual — made in 1964, and his first feature to reach the West — remains one of the supreme works of the Soviet sound cinema, and even subsequent Paradjanov features have failed to dim its intoxicating splendors. Set in the harsh and beautiful Carpathian Mountains, the movie tells the story of a doomed love between a couple belonging to feuding families, Ivan (Ivan Nikolaichuk) and Marichka (Larisa Kadochnikova), and of the subsequent life and marriage of Ivan after Marichka’s death. The plot is affecting, but it serves Paradjanov mainly as an armature to support the exhilarating rush of his lyrical camera movements (executed by master cinematographer Yuri Illyenko — who became one of Paradjanov’s best friends and allies, and later shot a feature based on one of his stories, Swan Lake —- The Zone, shortly before Paradjanov’s death), his innovative use of nature and interiors, his deft juggling of folklore and fancy in relation to pagan and Christian rituals, and his astonishing handling of color and music.

A film worthy in some respects of Alexander Dovzhenko, whose poetic vision of Ukrainian life is frequently alluded to, Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors also evokes fairy tales in general and even at times some of Walt Disney’s animated representations of their settings: the cottage of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs may only have an accidental resemblance to some of the cottages here, yet some of the same other-worldly atmosphere is felt. Yet the visceral physicality of many other shots is no less unmistakable, exemplified by a startling early shot which places the camera on top of a tree that has just been chopped– hurtling towards the ground and taking the viewer with it on its vertiginous plunge.

Slacker

Richard Linklater’s delightfully different and immensely enjoyable second feature (1991, 97 min.) — which is the first one that got any substantial distribution, after the more obscure and more obviously cinephiliac super-8-millimeter opus It’s Impossible to Learn To Plow By Reading Books (1989) — takes us on a 24-hour tour of the flaky dropout culture of Austin, Texas, which has remained Linklater’s headquarters ever since, throughout his multifaceted career. Unlike all his subsequent films to date, it doesn’t have anything resembling a continuous plot except in the most literal way that it moves chronologically and geographically through part of a day in Austin, but it’s brimming with weird characters and wonderful talk (which often seems improvised, though it’s all scripted by Linklater, apparently with the input of some of the participants, as in his later Waking Life). The structure of dovetailing dialogues calls to mind an extremely laid-back variation of Luis Buñuel’s The Phantom of Liberty or Jacques Tati Playtime, in which various events are glued together simply by virtue of appearing in proximity within the same patch of space and time.

Combining a certain formal logic with an illogical drive towards spinning out gratuitous fantasies and digressions is an impulse that follows Linklater through many of his subsequent pictures, but it’s likely that this combination has never been displayed quite as brazenly as it is here.

“Every thought you have fractions off and becomes its own reality,” remarks Linklater himself to a poker-faced cabdriver in the first (and in some ways funniest) sequence, again anticipating Waking Life by spouting fanciful philosophy from the back seat of a car. And the remainder of the movie amply illustrates this notion with its diverse paranoid conspiracy and assassination theorists, serial-killer buffs, musicians, cultists, college students, pontificators, petty criminals, street people, and layabouts (around 90 in all). Even if the movie goes nowhere in terms of narrative and winds up with a somewhat arch conclusion, the highly evocative scenes give an often hilarious sense of the surviving dregs of 60s culture and a superbly realized sense of a specific community.

There’s Something About Mary

Despite my earlier reservations about Bobby and Peter Farrelly, the brothers behind Dumb and Dumber and Kingpin, they’re progressively winning me over, partly because they keep getting better; this 1998 comedy often had me in stitches. Their gross-out humor is basically sweet tempered, for all its tweaking of PC attitudes, and though this film looks slapdash, its script (by the Farrellys, Ed Decter, and John J. Strauss) is surprisingly well put together. The victimized hero (Ben Stiller) nurtures a 13-year infatuation with the title heroine (Cameron Diaz), who’d moved away to Miami soon after high school in Rhode Island. He hires a shady detective (Matt Dillon) to track her down, and the detective falls in love with her himself. This movie’s unforced feeling for lower-middle-class disaffection is worthy at times of W.C. Fields, and there are some worst-case-scenario sequences involving a prom date, a dog, and jerking off that are convulsively hilarious; I also grew inordinately fond of Jonathan Richman and his drummer, the two klutzy musicians who periodically reappear, like the minstrels in Cat Ballou. With Lee Evans and Chris Elliott.

The Story of a Cheat

Widely regarded as Sacha Guitry’s masterpiece (though I’d place it below The Pearls of the Crown), this 1936 tour de force can be regarded as a kind of concerto for the writer-director-performer’s special brand of brittle cleverness. After a credits sequence that introduces us to the film’s cast and crew, Guitry settles into a flashback account of how the title hero learned to benefit from cheating over the course of his life. A notoriously anticinematic cineaste whose first love was theater, Guitry nevertheless had a flair for cinematic high jinks when it came to adapting his plays (or in this case his novel Mémoires d’un tricheur) to film, and most of this movie registers as a rather lively and stylishly inventive silent film, with Guitry’s character serving as offscreen lecturer. Fran çois Truffaut was sufficiently impressed to dub Guitry a French brother of Lubitsch, though Guitry clearly differs from this master of continental romance in the way his own personality invariably overwhelms that of his characters.

Tampopo

The late Juzo Itami called his second comedy (1987, 114 min.) a “ramen Western”. (Ramen are Chinese noodles —- a Japanese fast-food craze roughly akin to pizza in the U.S.) It represents a quantum leap from his already impressive first comedy, The Funeral (1984); the films that succeeded it, on the other hand, proved to be less adventurous, even though many of them were even more commercially successful in Japan. Without abandoning the flair for social satire that he showed in The Funeral (and continued to show in subsequent work), Itami expanded his scope in Tampopo to encompass the kind of free-form narrative play we associate with the late work of Luis Buñuel. His subjects are food, sex, and death, roughly in that order, his ostensible focal point the opening of a noodle restaurant. He takes us on a wild spree through an obsession, winding his way through various digressions with a dark, philosophical wit that is both hilarious and disturbing.

The title heroine (Nobuko Miyamoto, the director’s wife), preoccupied only with food, is a widowed mother determined to master the art of ramen with the aid of a mentor named Goro (Tsutomu Yamazaki), a truck driver. Her story is interlaced with that of nameless wealthy gangster dressed in white and accompanied by a white-clad mistress, who is preoccupied with food, sex, death, and cinema, most often in combination with one another. (We initially see him sitting down in the front row of a movie theater, before a sumptuous array of food, ostensibly preparing to watch the story of Tampopo.) And various digressions extend these intertwining themes to incorporate such Japanese standbys as deception, poverty, family, and guilt.

Itami works with a venerable cast that includes veterans of Akira Kurosawa, Yasujiro Ozu, Masahiro Shinoda, and Shuju Terayama, and it seems likely that these earlier associations play a role in his overall comic scheme. (Yamazaki, for instance, was the kidnapper in Kurosawa’s High and Low, and a teacher of table manners was the heroine’s kid sister in Ozu’s An Autumn Afternoon.) As in The Funeral, Itami’s ultimate interest appears to be exploring as well as ridiculing some of the paradoxes of Japanese society, including those involving class and etiquette, and he carries this off with energy and inventiveness.

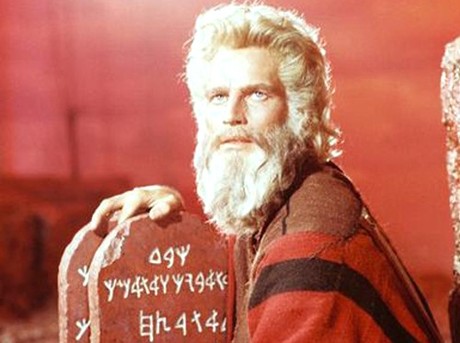

The Ten Commandments

With a running time of nearly four hours, Cecil B. De Mille’s last feature and most extravagant blockbuster is full of the absurdities and vulgarities one expects, but it isn’t boring for a minute. Although it’s inferior in some respects to De Mille’s 1923 picture of the same title (which, under the likely influence of D.W. Griffith’s 1916 Intolerance, used the story of Moses as an extended prologue to a contemporary tale) and some of the special effects look less plausible now than they did in 1956, the color is ravishing, and De Mille’s form of showmanship, which includes his own narration, never falters. Charlton Heston might be said to achieve his apotheosis as Moses —- unless one decides that it’s Moses who’s achieving his apotheosis as Heston —- and most of the others in the cast are comparably mythic, including Anne Baxter, Edward G. Robinson, Yvonne De Carlo, Debra Paget, John Derek, Vincent Price, John Carradine, and Woody Strode as the king of Ethiopia.

Simultaneously ludicrous and splendid, this is an epic driven by the sort of personal conviction one almost never finds in subsequent Hollywood monoliths. To read it properly, one has to see it as an ideological as well as spiritual manifesto relating specifically to how De Mille viewed the cold-war world in 1956. Thus, when he appears in front of a gold-tasseled curtain to introduce the film, his main point isn’t simply his use of ancient sources such as Philo and Josephus to recount the 30 years of Moses’s life omitted in the Bible, but also to declare that “The theme of this picture is whether man should be ruled by God’s laws or…by the whims of a dictator like Ramses.” By “dictator,” he’s clearly thinking of someone like Mao Tse-tung, which the orientalism suggested by Yul Brynner as Ramses makes clear.

Shot in VistaVision, the film has sometimes been rereleased —- most recently, in 1990 — in a stretched, anamorphic widescreen format, which means that the top and bottom of every frame is cropped. There may be some form of divine retribution at work here; De Mille was a notorious foot fetishist, and thanks to this studio skullduggery, many of De Mille’s foreground players have now been deprived of their feet.

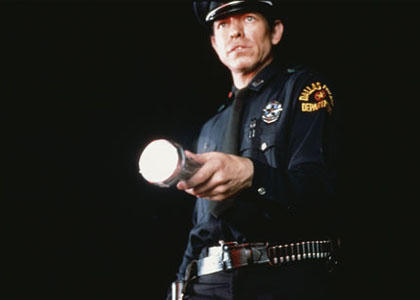

The Thin Blue Line

Errol Morris’s third documentary feature (after Gates of Heaven and Vernon, Florida) is an absorbing if problematic 1988 reconstruction of and investigation into the 1976 murder of a Dallas policeman. As an investigative detective-journalist who spent many years working on this case, Morris uncovered a disturbing miscarriage of justice in the conviction of Randall Adams — who came very close to being executed, and was saved as a result of this film. Morris goes so far in his talking-head interview technique that he eventually goads David Harris, Adams’s companion on the night of the murder, into something very close to a confession. It’s the latter achievement that makes this film as memorable and as important as it is. But it’s worth bearing in mind that Morris’s highly selective approach also leaves a good many questions hanging. The issue of motive is virtually untouched, and the quasi-abstract re-creations of the crime, accompanied by what is probably the first effective film score ever composed by Philip Glass, give rise to a lot of metaphysical speculations that, provocative as they are, only obfuscate many of the issues about what actually happened.

The results are compelling, even though they provide an object lesson in the dangers of being influenced by Werner Herzog; the larger considerations and the film noir overtones wind up distracting us from the facts of the case, and what emerges are two effective half-films, each of which is partially at odds with the other. Yet one can also see Morris honing his flair for juxtaposition and editing that would eventually bear fruit in his remarkable Fast, Cheap & Out of Control (1997), where he manages to juggle the continuities and discontinuities between four seemingly unrelated talking heads, and in the multiple achievements of his episodes in the TV series First Person, which has already enjoyed two seasons.

Three Lives and Only One Death

Perhaps the most accessible movie of the Chilean-born Raul Ruiz (who has over a hundred titles to his credit) — a sunny showcase for the charismatic talents of the late Marcello Mastroianni, who plays four separate roles, as well as a testament to Ruiz’s imaginative postsurrealist talents as a yarn spinner and a weaver of magical images and ideas. Mixing ideas borrowed liberally and freely from stories by Nathaniel Hawthorne and Isak Dinesen with whimsical notions that could belong to no one but Ruiz (such as the tale of a millionaire who willingly and successfully turns himself into a beggar), this 1996 French comedy with a Paris setting often resembles a kind of euphoric free fall through the works and fancies of a writer like Jorge Luis Borges. Among the spirited cast members are Mastroianni’s daughter Chiara, Melvil Poupaud (who played in Ruiz’s City of Pirates), Anna Galiena, Marisa Paredes, and Arielle Dombasle. Pascal Bonitzer is the cowriter.

Through the Olive Trees

The social status of filmmaking among ordinary people, central to Abbas Kiarostami’s wonderful Close-up and Life and Nothing More, is equally operative in this entertaining and sometimes beautiful film. Through the Olive Trees (1994) concludes an unofficial trilogy begun with Where Is the Friend’s House?, which focused on the adventures of a poor schoolboy in a mountainous region of northern Iran. Life and Nothing More, the second of the three, fictionally re-created Kiarostami and his son’s return to the area, which had recently been devastated by an earthquake, to look for two child actors from the earlier film. Through the Olive Trees is a comedy about the making of a film, mostly emphasizing the persistent efforts of a young actor to woo an actress who won’t even speak to him. Like Kiarostami’s subsequent recent Taste of Cherry, all three films strategically elide certain information about the characters, inviting audiences to fill in the blanks and in this case yielding a mysteriously beautiful and open-ended conclusion. If you’ve seen the two earlier pictures, some details are enhanced: the child actors who are never found in Life and Nothing More, for instance, turn up as gofers here, carrying flower pots to a location.

On the other hand, if you’re unfamiliar with Kiarostami — one of our greatest living filmmakers and certainly the greatest in Iran — this is an excellent introduction, and it has served that function for many viewers across the globe (excluding, for the most part, the United States, where the distributor Miramax picked up the film only to bury it, making it the hardest to see of Kiarostami’s late features). It was the first of his European coproductions and has the only professional actor he’s ever hired for any of his films. Mohammad-Ali Keshavarz as the director. It’s an especially effective showcase for Kiarostami’s gifts as a landscape artist, having been shot exclusively in exteriors, and the beautiful ways that he interweaves conversations in cars moving through this mountainous region and the people and other sights that they pass on the road are often breathtaking.