From Cinema Scope issue 39, Summer 2014. — J.R.

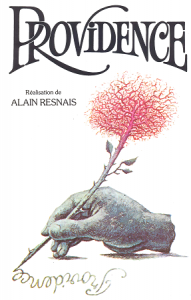

I shelled out $56.19 in US dollars (including postage) to acquire the definitive and restored, director-approved DVD of Providence (1977) from French Amazon, and I hasten to add that this was money well spent. Notwithstanding the passion and brilliance of Alain Resnais’ first two features, Providence is in many ways my favourite of his longer works, quite apart from the fact that it’s the only one in English. And I can’t ascribe this preference simply to the contribution of David Mercer (1928-1980). I recently resaw the only other Mercer-scripted film I’m familiar with, Karel Reisz’s Morgan!, and aside from the wit of its own sarcastic dialogue I mainly found it just as flat and tiresome as I did in 1966, for reasons that are well expounded in Dwight Macdonald’s contemporary review (reprinted in his collection On Movies).

I haven’t yet been able to see The Life of Riley (Aimer, boire et chanter), Resnais’ swan song, but clearly part of what gives Providence even more resonance now, writing less than a month after Resnais’ death, is the theme it shares with his penultimate feature, You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet (2013): an old writer facing his own death, and trying to create some form of art in relation to it. (John Gielgud’s performance as the old writer is for me one of the greatest bits of film acting that we have, and Dirk Bogarde’s superb rendition of the writer’s emotionally repressed older son may be as much of a self-portrait on Resnais’ part.)

The DVD has some fascinating extras: François Thomas’ very informative 29-minute audio interview with Resnais about the film (which Resnais conceived from the outset as a “documentary about imagination”) and a 51-minute documentary including detailed interviews with art director Jacques Saulnier, cinematographer Ricardo Aronovich, and actor Pierre Arditi (who doesn’t appear in Providence, but whose work with Resnais in countless other films still gives him plenty to talk about), both thoughtfully provided with optional English subtitles. The single-disc set also includes both the original English and the French post-dubbed versions of the film (the latter of which Resnais supervised, and which includes many of the most famous actors in French cinema, even though the lip-sync isn’t always up to the line readings).

On the box is a quote from Norman Mailer, of all people: “Le meilleur film jamais réalisé sur le processus de création,” which translates as “The greatest film ever made on the creative process,” and it’s surely telling that I had to go to a French source to come upon such an apt and just description of this vibrant masterpiece. On the other hand, go to James Wolcott, one of Mailer’s protégés, and you’ll find him actually bragging about helping to create a ruckus with another of his mentors, Pauline Kael, at a New York press screening for having “dared take Alain Resnais’ Providence (a meditation on death and creativity endorsed by Susan Sontag, swinging her incense ball) less than solemnly.” I guess those fearless pranksters and indefatigible truth-tellers just didn’t dig how much of Providence is a comedy. Too bad I was off in Europe during most of the mid-’70s; otherwise I might have been around to hoot and jeer at Kael and Wolcott swinging their own solemn incense balls to greet the far less witty and neo-Stalinist, power-worshipping pomposity of The Godfather Part II (1974).