My introduction to my 1997 collection MOVIES AS POLITICS. — J.R.

A feeling of having no choice is becoming more and more widespread in American life, and particularly among successful people, who are supposedly free beings. On a concrete plane the lack of choice is often a depressing reality. In national election years, you are free to choose between Johnson and Goldwater or Johnson and Romney or Reagan, which is the same as choosing between a Chevrolet and a Ford — there is a marginal difference in styling. Just as in American hotel rooms you can decide whether or not to turn on the air conditioner (that is your business), but you cannot open the window.

— Mary McCarthy, Vietnam, 1967

I await the end of Cinema with optimism. — Jean-Luc Godard, Cahiers du cinéma, 1965

Thirty years later, both these general sentiments describe an impasse in American life that is vividly reflected in the movies we see and the ways that we see them. If the range of cultural choices apparently available at any given time merits some correlation with the range of political choices, it is also true that Godard’s optimistic apocalypse heralds a new scale of values, though we don’t yet know enough about these to be able to judge them with any confidence. Whether we condemn or applaud the prospect, a first priority might be a simple evaluation of where we are.

It probably isn’t being presumptuous to assume that, in one way or another, as we near the century’s end, everyone reading these lines is awaiting the end of some kind of cinema, either optimistically or pessimistically. Whatever name or interpretation we give to this climate, we all feel that something is in the process of ending — unless we feel that it has ended already. Something is also in the process of beginning; but whatever we choose to call it, I don’t think we can call it cinema in the old sense. The rapid spread of movies on video, the astronomical escalation of movie advertising, the depletion of government support for film preservation or new independent work (never very large to begin with), the return to a system of theater monopolies and the concomitant phasing out of independent exhibition (which allows for such alternative fare as art films and midnight movies) — what amounts, in short, to the junking of an already precarious film culture in the interests of short-term financial gains for big business — suggest a historical period being sealed off, so that the past isn’t only another country but a different planet, a different language, a different set of aspirations. Like Mary McCarthy, we can learn this new language well or badly and say all kinds of different things with it, but we can’t use it to lead us back to cinema in the old sense (cinema, let us say, that was still on speaking terms with the era of Griffith, Murnau, and Stroheim). That’s a window that has been nailed shut, and unless we break through the glass — destroy the institutions and the technology that separate us from the past — we have to get used to living in air conditioning.

***

With only a few modifications, the above was written over a decade ago — first for a lecture at the Rotterdam Film Festival’s Market in January 1985, then for an article published in Sight and Sound the following summer. The fact that much of what I said then still seems applicable suggests not so much a protracted death rattle for cinema as a certain freezing over of film history itself, at least as it’s usually being recounted.

I’m writing now in the fall of 1995, when the recent number one box office hit is SEVEN, a stylish, “metaphysical” serial-killer movie whose designer grimness can be said to carry a certain ideological comfort: if mankind is hopelessly blighted and evil is both omnipresent and triumphant — expressionist notions virtually carried over like dress styles from TAXI DRIVER (1976) and BLADE RUNNER (1982) — then it stands to reason that political change isn’t even worth hoping for and that legislation designed to make millionaires richer while increasing the suffering of the homeless is the only “realistic” kind we can contemplate. Yet if we accept this made-to-order postulate, we have to overlook the fact that SEVEN originally had an even grimmer ending than it does now — an ending revised as soon as preview audiences objected. We have to consider, in short, that the ideological demands made of entertainment are no more contradictory or foolish than those made of government or the news in general, and that these are usually based on short-term guesses about what makes us feel good, not long-term investments in what might make us stronger or wiser.

After all, only a few years ago, during the Gulf War, there was another serial-killer movie that helped to create the vogue for SEVEN: THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS. What seemed horrific to me at the time about the specious claim that this movie was teaching us something important about evil or psychosis or violence was that it was being made just as we were gleefully devastating a country and people already oppressed by a dictator — mainly, it seemed, for the sake of holding a weapons trade fair. So our fascination with one individual, Hannibal Lecter, killing without compunction, may have betrayed a certain unconscious narcissism on our part; in fact, that crazy shrink had nothing on us. Moreover, our censored war news at the time also focused mainly on one demonic individual, Saddam Hussein, and clearly all the corpses we and he were creating were made to seem secondary. This was star politics with a vengeance, and when Anthony Hopkins was eventually handed an Oscar, it was oddly evocative of the standing ovation George Bush received in Congress.

A few months later, TERMINATOR 2: JUDGMENT DAY brought back THE TERMINATOR’S former villain, the Arnold Schwarzenegger robot, this time as a hero — neatly echoing Bush’s own reversals of policy (albeit in the opposite direction) toward Saddam in the Gulf and, two years earlier, Noreiga in Panama. In all three cases, the euphoria of watching a mean machine plow through everything in its path — whether this was Panama City, Baghdad, or an American freeway — clearly mattered more than whether the machine happened to be a Good Guy or a Bad Guy.

In all three of the examples offered above, there’s an effort to link a recent movie with events that are contemporary with it — signaling one of the several polemical approaches to film and politics taken in this book, one that partially echoes the readings given to certain movies I saw as a child in my 1980 memoir, Moving Places (2d ed., 1995). It could be argued, of course, that because neither Thomas Harris’s best-selling novel nor Jonathan Demme’s movie is in any way inspired by the Gulf War, my juxtaposition of that war with the reception of THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS simply and arbitrarily imposes my own political program on this material. “Keep your politics out of your reviews,” wrote an irritated reader in 1993 (as if he or I had a choice in the matter). “It’ll destroy your credibility.” But keeping politics out of movie reviews, I’d argue, is precisely what makes it easy to cheer and celebrate such CNN “movies” — or “turkey shoots” — as OPERATION DESERT STORM and WAR IN THE GULF.

***

Indeed, a central issue in this book is how closely our news resembles our so-called entertainment and vice versa; and what sort of relation either sphere bears to reality sometimes turns out to be my main subject. Those who question my description of STAR WARS as “a guiltless celebration of unlimited warfare” may want to consider that my piece was written well before that movie title was used to identify a U.S. military weapons program. It might be argued that this proves nothing apart from Ronald Reagan’s fondness for movie references, but my main purpose here and elsewhere in this book is to argue that what is designed to make people feel good at the movies has a profound relation to how and what they think and feel about the world around them.

***

Like my previous collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995), this volume contains reviews and essays written since the early 70s, but on this occasion I have sought to place them all within a political context — a context of placing movies politically, which also means describing one particular version of what movies are and can be in the 90s. (Movies as politics also generally means movies as history, including an effort to deal with the present historically.) It entails looking not just at the political implications of many different kinds of films as “statements” and processes in themselves but also at the political aspects of what might be called the challenge of cinema — its aesthetic forms, its narrative tactics, and its patterns of production, promotion, distribution, exhibition, and reception. About two-thirds of the pieces here first appeared in the Chicago Reader, and though some have been revised and updated, I’ve retained local references whenever they seemed relevant, trusting that non-Chicagoans will still be able to follow the drift.

A touchstone throughout my career has been George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language,” an essay that draws explicit and useful links between writing style and political thought (or its absence). In my first section, I seek to extend this mode of perception by discussing the political implications of film form as well as film style. To some extent, this approach runs through the remainder of the book; it can even be found in my study of Bresson’s LANCELOT DU LAC, where it may seem least apparent. For it is my belief that formal procedures — by shaping and ordering our perceptions, by determining how we engage with art as well as life — are always grounded in political decisions of one kind or another, whether we choose to recognize them or not. Contrary to the debilitating American idea that politics are only a matter of elections (and therefore something to be avoided), accepting or rejecting the status quo when it comes to filmgoing is already a political decision in the most basic way, and deserves to be treated as such. For that matter, honoring film as an art or regarding it basically as a form of light entertainment is very much a political issue — though many would call it just a matter of “taste” — and I suspect that my own bias for the former attitude over the latter lies at the root of what makes many of my other positions controversial to some.

How, indeed, do the roles played by sound and image in relation to one another — an important concern in my piece on LANCELOT — function politically? In several ways, I would argue. Though formalist analysis often avoids this, it seems to me that formal innovation is often a matter of finding ways to discover and articulate new kinds of content, to say things that otherwise couldn’t be said, find things that otherwise couldn’t be found. This is only speculation, but it seems to me that many of Bresson’s hallmarks as a filmmaker — such as his uses of offscreen sounds to replace images and the sense found in all his films of souls in hiding, of buried identities and emotions — might be traceable in part to his nine months (1940–1941) as a POW in a German concentration camp and his subsequent experience of the German occupation of France. I’m thinking not only of his masterpiece about the French resistance, A MAN ESCAPED (1956) — where the sounds of the world outside the hero’s prison cell create as well as embody his very notion of freedom — but also of LES DAMES DU BOIS DE BOULOGNE (1945), made during the Occupation itself. Speaking recently to the film historian Bernard Eisenschitz, Jean-Luc Godard provocatively called LES DAMES the “only” film of the French Resistance, and in chapter 3A of his video series HISTOIRE(S) DU CINEMA, he cites Elina Labourdette’s penultimate line in the film, “Je lutte,” to make a similar point. Such an interpretation can of course be debated, but it seems to me a far more fruitful approach to Bresson’s style to see it growing out of a concrete and material historical experience than to treat it as a timeless, transcendent, and ultimately mysterious expression of abstract spirituality.

***

Responding to Theodor Adorno’s critique of Stravinsky, Milan Kundera writes in

Testaments Betrayed:

What irritates me in Adorno is his short-circuit method that, with a fearsome facility, links works of art to political (sociological) causes, consequences, or meanings; extremely nuanced ideas (Adorno’s musicological knowledge is admirable) thereby lead to extremely impoverished conclusions; in fact, given that an era’s political tendencies are always reducible to just two opposing tendencies, a work of art necessarily ends up being classified as either progressive or reactionary; and since reaction is evil, the inquisition can start the trial proceedings.[*]

[*] Translated from the French by Linda Asher (New York: HarperCollins, 1995), 91.

I don’t know if this argument is fair to Adorno (I suspect it may be guilty of the kind of mechanical critique it’s decrying), but I’d prefer to think it doesn’t apply to any of the essays here, even though the issue of “political correctness” might be raised — indeed, has been raised — in relation to some of them. The novelist Paul Auster, a former acquaintance in Paris in the mid-70s, suggested when I ran into him at a film festival two decades later that PC was the gist of my objection to SMOKE in “The World According to Harvey and Bob,” after explaining that he had fought a battle of his own (successful in his case) to prevent Miramax from recutting the film.

The problem with a term like PC is that it’s no more neutral than the social realities it’s supposed to be grappling with. To my mind, there’s a PC of the right — in which conservatives like Clarence Thomas and O. J. Simpson both potentially figure as affirmative action beneficiaries — as well as a PC of the left, and in both cases it generally represents a rejection of real politics for the sake of symbolic politics, a politics of representation in which fantasy “role models” usually serve to obfuscate and avoid real issues. In the cases of SMOKE and THE GLASS SHIELD, where I’m chiefly interested in the processes by which both films got defined as well as judged in the mainstream, THE GLASS SHIELD — which shows its black hero committing perjury against another black man — is surely even more “politically incorrect” than SMOKE. (I’m reminded of the objection I once heard made to Danny Glover at a Chicago screening of Burnett’s previous feature, TO SLEEP WITH ANGER, for not playing a suitable “role model” for black children in that film — a remark that provoked his understandable ire.) Indeed, my objection to William Hurt and Harvey Keitel in SMOKE is precisely that they do provide fanciful white role models and feel-good PC figureheads rather than characters designed to provoke any deep understanding of the complexity of American race relations.[*]

[*] For a devastating critique and wholly convincing analysis of such characters, see Benjamin De Mott’s indispensable The Trouble with Friendship: Why Americans Can’t Think Straight About Race (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1995).

As a critic, I tend to deal with certain aspects of the mainstream from an outsider’s position and, conversely, to look at alternative forms of filmmaking from a mainstream position. In the interests of both acknowledging and challenging the usual ghetto boundaries that inform our reception of films, I have highlighted this dichotomy by placing most of my treatments of well-known and recent Hollywood movies in the middle of the book. In a couple of cases, I’ve even included non-Hollywood pictures in this section if the notion of a Hollywood actor (Keitel in THE PIANO) or a Hollywood studio (Disney, which owns Miramax, the distributor of SMOKE and THE GLASS SHIELD) remains operative in how a picture is received.

A related dichotomy in our film culture, between the marketplace and academic film study, is the central concern of both of the book review essays included — one on musicals in the first section, the other on two collections of articles in the third section. One can also find an impulse recurring throughout the book to stage certain “shotgun marriages” in relation to specific topics: STAR WARS seen in light of some of the political films of Jean-Luc Godard, French serials by Louis Feuillade and Jacques Rivette, a Gypsy musical seen in relation to Hollywood musicals, the operations of chance in films by Robert Altman and Rob Tregenza, and so on.

Recognizing that some readers are reluctant to read about movies they haven’t seen — though also realizing that maintaining silence about unavailable films helps to keep them unavailable — I’ve placed more emphasis in this volume on movies that are widely known, while hoping that some readers engaged by this sandwich filling will be moved to try my bread slices as well, part of which propose a much wider definition of “the cinema” than the mass media generally allow (including even two videos in “Alternate Histories,” although paradoxically both of these are concerned with cinema). An earlier book of mine is devoted to surveying various North American and European independent filmmakers; this one revives part of that concern, and even extends it to such non-Hollywood outposts as Asia and Africa, but I have still tried to keep much of this book within hailing distance of more common reference points. “Alternate Histories” — a subgrouping of five final essays, partially predicated on the notion that the future of cinema depends to some extent on our acquaintance with its past — is devoted specifically to adventures in research, which for me has always comprised a major part of criticism. (This is at once the most tentative and the most utopian section in the book.) Another major part, mainly discernible in more recent pieces, is an effort to use films as a way to speak about other things in our society: racism, xenophobia, targeting, tribalism, feminism, illness, urban social engineering, postmodernism, sexual obsession, and class divisions, among several other topics.

Unlike my books Moving Places and Placing Movies, Movies as Politics has no explicit autobiographical agenda, but readers will see that autobiography frequently plays an important role in my critical methodology; it is even, I would argue, central to its politics. One reason for forcing myself into the picture is quite simply to make the criticism more usable by contextualizing my positions and showing where they come from — refusing to resort to hidden agendas, and respecting the reader’s right to disagree. Another reason is that I believe movies are potentially important enough to be tested in relation to life, not simply accepted as loose approximations or escapist alternatives — a point made in my considerations of MISSISSIPPI BURNING, SAFE, CRUMB, and BLOOD IN THE FACE, among other pieces.

The reviews and essays included here were written between 1972 and 1995, and some readers may conclude that the pieces that come closest to being formalist, such as those on Bresson and Altman, were written toward the beginning of this period, when I was still living in Europe (Paris and London) and arguably had fewer overt political ties to my immediate surroundings. One of the most interesting political lessons I learned from my years abroad (1969–1977), however, was that sensitivity to formal issues doesn’t necessarily entail an avoidance of political issues. To put it bluntly, most of the critics I knew in Paris and London who were sophisticated about formal issues were communists, most often party members, while many of their stateside leftist counterparts were more likely to be philistines about such matters. Adapting some of the formal perceptions of European leftists to Anglo-American idioms has probably always been an important part of my contribution as a critic; see, for instance, my remarks in this book about DO THE RIGHT THING, PLAYTIME, LATCHO DROM, SAFE, OUT 1, and the films of Mike Leigh and Cy Endfield.

***

Are there times when one’s aesthetic responses and one’s politics are in conflict? Certainly, and some of the reviews in this book — notably those of SCHINDLER’S LIST, REDS, PULP FICTION, LA MAMAM ET LA PUTAIN, and SOLARIS — are devoted in part to trying to pinpoint and clarify those conflicts. Hardly anyone can claim to be reducible to his or her political positions at all times, especially at the movies, but the moments when conflicts or contradictions arise usually prove to be highly instructive. Part of my ambition in these essays is to create a mode of inquiry in which honesty about such matters becomes both possible and desirable.

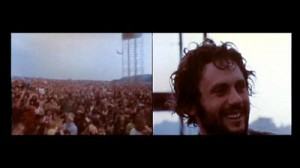

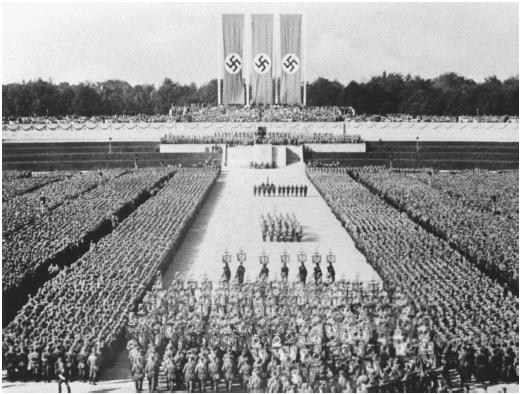

Case in point: Writing about Michael Wadleigh’s WOODSTOCK in 1970, I decided that the movie was really the counterculture’s equivalent to Leni Riefenstahl’s TRIUMPH OF THE WILL, and mentioned this conceit in print several times afterward. Although I liked the film, it seemed worth tweaking some of the things I liked about it: its epic shape and canvas, its teeming crowds, its awestruck euphoria, its adoring low-angles of charismatic performers, plus the fact that it was a film record of an event planned in part for the purpose of making a movie. My point was mainly aesthetic, but I wanted the ideological ramifications to give the reader some pause. Then, after noticing, when WOODSTOCK was rereleased in 1994, that many of my colleagues were making the same comparison, I started to wonder if for some of them the similarity was more ideological than aesthetic — especially when they compared WOODSTOCK unfavorably with GIMME SHELTER, a film I’ve always disliked political and aesthetically for its self-serving “critique” of the counterculture. A comparison that for me in the 70s and 80s was an ironic form of praise was used by others in the 90s as a straight putdown.

How political was WOODSTOCK in 1970? When I saw it at the Cannes film festival, Wadleigh dedicated the film to the four students killed by National Guardsmen at Kent State only five days earlier; when the screening was over, he stood by the exit doors and passed out black armbands. I took one myself, but two days later some boutiques in Cannes started selling similar armbands. What had seemed political on Saturday had become a sort of marketing device by Monday; it was a key early lesson for me in movies as politics. And the next twenty-five years provided an education outlined in this book.

— J.R, December 1995