From the Bard Observer, March 30, 1964. The greatest teacher I’ve ever had, by far, was Heinrich Blücher, the husband of Hannah Arendt, who taught for many years at Bard College, and this was one of the two pieces of mine in the Bard Observer that he made a point of telling me that he liked. (The other one was an extended personal report on the Montgomery March that had appeared the previous spring.) From my present vantage point, I think this may have been my first really serious film review. I’ve done a light edit on it while transcribing it. -– J.R.

“Doctor Kubrick”: or How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love the Movie

By JON ROSENBAUM

The story is from Peter George’s Red Alert….A crazy American general sends a squadron of nuclear bombers to get in a first strike at Russia; after frantic efforts and unspeakable confusion, the American President manages to recall or have destroyed by the Russians all but one; this gets through and drops its bomb, which triggers off a nuclear death belt the Russians have secretly contrived; the picture ends with the world due to follow shortly.

— from a review of Dr. Strangelove

Somehow, the idea has gotten around that Dr. Strangelove is a comedy. Stanley Kubrick, the film’s director, has made a few statements to advance this belief; the press has conscientiously showered us with reassuring testimonies to the fact; and. indeed, after having seen the film, I find it difficult to conceive of any one sitting through it without laughing. Nevertheless, I feel that the term “comedy” –- which is used nowadays to identify everything from Twelfth Night to the Three Stooges — has become so bereft of meaning that it seems an injustice to shuffle Kubrick’s work in with all the others that have ever begged that label. Whatever one could call the film, it is not another “lafforama” -– one of those BilIy Wilder express trains like One, Two, Three, which encourages us to dismiss our anxieties by laughing about them. Kubrick lets us have our cake, all right, but he who tries to eat it will likely wind up choking.

A number of reviews have spoken about Strangelove as if it were a congenial exercise in audience therapy. (“All kidding aside, movie fans, it’s a very funny film that squeezes plenty of chuckles out of what is basically a serious matter — i.e., nuclear destruction. If the real thing happened, of course, it wouldn’t be much of a laughing matter, but as long as the idea remains conjectural, there’s still room enough for man to keep his Innate Sense of Humor — which is, after all, what makes him Human — and Laugh at his own Petty Foibles.”)

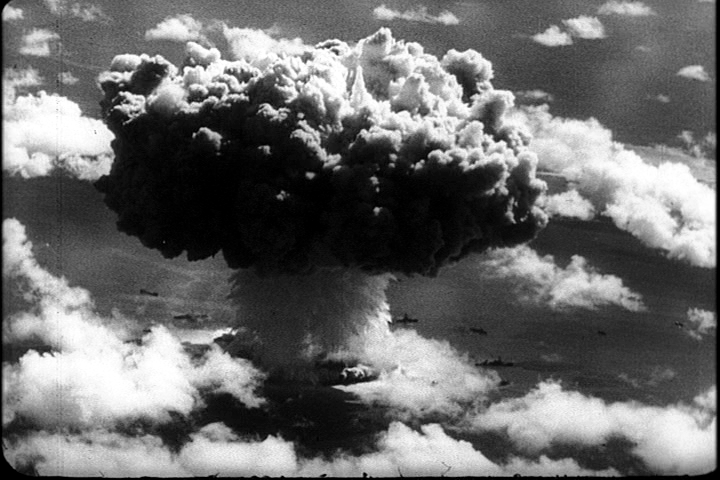

If this quality — this bland assumption that Kubrick is gently poking us in the ribs — was anywhere evident in Dr. Strangelove, it would probably be a very satisfying movie. As it stands, it is something much less than that, and much more: it comes close to obliterating our sense of humor in the process of exploiting it. If we are still laughing at the end of the movie, this is not,I think, because we are still amused; rather it is because Kubrick has convinced us of the impossibility of any other reaction. For StrangeIove is more than a dissertation on the absurdity of the arms race, more than a political club designed to bludgeon us out of complacency; it is a film not about the Bomb but about men. The Bomb itself is relatively harmless: when it makes its eventual appearance near the film’s close and sprouts a graceful mushroom, the effect is somewhat superfluous, for the point has already been made.

To any one familiar with Kubrick’s previous films (which include The Killing, Paths of Glory, and Lolita, as well as Spartacus, which he disowns as a strictly commercial project), his career exhibits the sustained energies of a misanthrope, tempered always with the most brutal kind of humor; he is the only director I can think of who would have tried to make the hero of Lolita more comically pathetic than he already was in the book. This film was at best a collection of unconnected pieces, but Kubrick was able to infuse parts of it with a fresh, anxiety-ridden brand of comedy which Peter Sellars beautifully implemented, and which is brought to fruition in Strangelove. It is a comic technique which produces anxiety in the audience as well as in the actors, and it finds no fuller or more frightening image than in the figure of Dr. Strangelove, who is brought into full play only at the film’s conclusion.

The character of Strangelove is central to the film’s theme and final impact, but this is mainly due to the proliferation of scenes and characters that precede his appearance. Up to the point when the bomb is dropped, we are treated to a rapid succession of farcical events. General Jack D. Ripper, having become convinced of a Communist plot to take over the world through fluoridation (responsible for the pollution of our “precious bodily fluids”), launches a nuclear attack on Russia; the President calls a frantic meeting of his aides in the War Room, in an attempt to discover some method for recalling the bombers. The ensuing events are all treated satirically, and the targets are all easily discernible: Men are shown as victims of their own bureaucracy and incompetence, and the imminence of the Bomb increases as the camera continually cross-cuts from crazy general to War Room to bomber and back again. As the pace accelerates, the film moves toward a vision of total madness, but it is not until the actual dropping of the bomb that it completely realizes the ultimate target of its energies –- again, it is not the Bomb, it is not the bureaucracy, it is not the incompetence nor the insanity. It is the source from which all these aberrations sprang: mankind itself.

The bomb is released, and the commander of the plane, Major Kong (a Texan, played by Slim Pickens), wearing a cowboy hat and yelling ecstatically, rides the bomb down like a stallion. The camera takes a sudden downward plunge to dash after him, rushes towards the ground, and for a split-second, the screen turns completely white: there is a breath-stopping pause: and then the scene is switched back to the War Room, where Dr. Strangelove makes his final speech.

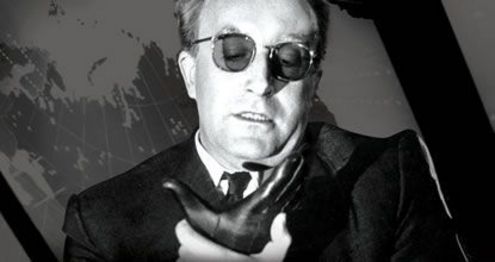

The doctor (played by Peter Sellars, who also handles two other roles) is a German scientist, presumably the consummate American bomb-expert, strapped in a wheelchair and sporting a nervous smile; physically, he is little more than an accumulation of twitches. As he begins to relate to the President his plans for creating an underground society, nervous laughs constantly interrupt his voice as often as his twitches, and his artificial hand begins to spring up involuntarily to make a Nazi salute. At this point it becomes clear that competence (or “expertise”) is as much an evil of Man as his lack of it; the view of Man that is concentrated in Strangelove is horrifying enough to make the Bomb look like a blessing rather than a threat. As he continues to talk, his hand keeps springing up until he is forced to direct all of his attention to keeping it down. Eventually it moves towards his throat and begins to strangle him; like mankind, he is a machine that has gone berserk. When, shortly afterwards, he springs out of his wheelchair with a cry of exaltation (“Mein Fuhrer! I can walk!”), we are offered some horrible insight into the only kind of victory that Kubrick believes man can achieve.

An argument can be made -– and indeed, has been made in several reviews -– that a comedy of this sort is sick and tasteless. This seems a confusion of disease with diagnosis; certainly the film abounds with sickness and an acute lack of taste, but we do not call a doctor “sick” or “tasteless” if he makes out a report that his patient has syphilis. It can also be argued that the film fails because it lacks an alternative to the madness it portrays (i.e., even Swift and Rabelais maintained some concept of the ideal). Since Dr. Strangelove is miles away from suggesting any ideals, I find this unanswerable, although it can be stated that it asks a sane mind to understand and recognize madness. Basically, I believe that the movie is hateful as far as it is successful, and unsuccessful insofar as it is likable; for its success depends on the strength of its vision and its ability to convince us, and I doubt seriously whether any of us is un-man enough to take it. As an experience, however, none of us is likely to forget it.