This book can now be purchased as a paperback for just under $28.00 (or less) on Amazon. — J.R.

It’s a genuine pity that this remarkable new book — a kind of summation and extension of Adrian Martin’s work in film analysis and the history of film criticism in Australia, France, Spain, the U.K., and the U.S. over the past two decades — is commercially available only at the whopping price of $80.75 on Amazon — or $76, if you’re willing to settle for a Kindle edition. As a longtime friend, colleague, and collaborator of Martin’s, I was fortunate enough to receive a free inscribed copy, but most of the rest of you will have to either shell out a fortune or wait for a softcover edition. All I can do now, really, having received this book only yesterday, is signal just a few of its many riches. Girish Shambu, Adrian’s irreplaceable coeditor at LOLA, has already posted a helpful summary of the book’s “four [interests] that animate the work” on his web site, so the most I can hope to do here is cite just a few treasured and brilliant passages that already have either sent me back to the films and texts being discussed or extended my current (re)reading and (re)viewing lists:

G. Cabrera Infante writing in 1957 about Tea and Sympathy (Vincente Minnelli, 1956), pp, 6-7.

G. Cabrera Infante writing in 1957 about Tea and Sympathy (Vincente Minnelli, 1956), pp, 6-7.

***

On a Clear Day You Can See Forever (Vincente Minnelli, 1970), pp. 48-53.

On a Clear Day You Can See Forever (Vincente Minnelli, 1970), pp. 48-53.

***

V.F. Perkins writing in 1969 and Kaja Silverman and Harun Farocki writing in 1998 about Vivre sa vie (Jean-Luc Godard, 1962), pp. 34-38.

V.F. Perkins writing in 1969 and Kaja Silverman and Harun Farocki writing in 1998 about Vivre sa vie (Jean-Luc Godard, 1962), pp. 34-38.

***

White Nights (Luchino Visconti, 1957), pp. 57-67.

White Nights (Luchino Visconti, 1957), pp. 57-67.

***

“The Essential” (Jacques Rivette writing about Preminger’s Angel Face in 1954), pp. 68-70.

“The Essential” (Jacques Rivette writing about Preminger’s Angel Face in 1954), pp. 68-70.

***

The Lady from Shanghai (Orson Welles, 1947), pp. 111-115.

The Lady from Shanghai (Orson Welles, 1947), pp. 111-115.

***

Force of Evil (Abraham Polonsky, 1948), pp. 116-119.

Force of Evil (Abraham Polonsky, 1948), pp. 116-119.

***

Before Sunrise (Richard Linklater, 1995), pp. 135-136.

***

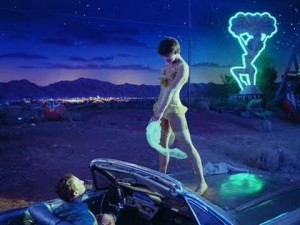

Serge Daney writing about One From the Heart (Francis Coppola, 1982), pp. 174-175.

Serge Daney writing about One From the Heart (Francis Coppola, 1982), pp. 174-175.

***

Though I’ve tried to strike an almost even balance above between texts by Martin and texts by others that he cites and discusses, I’ve cheated a little by neglecting to mention that two statements by Polonsky himself are also pivotal to the discussion of Force of Evil. I’ve also been limited by the illustrations I can find on short notice; otherwise, I could just as readily have cited Martin’s analyses of sequences from Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder (pp. 43-45), Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Martha (82-87 and 139-140), several Tsai Ming-liang films (pp. 90-94), Alan Rudolph’s The Moderns (pp. 98-101), John Ford’s How Green Was My Valley (pp. 147-154), Miguel Gomes’ Our Beloved Month of August (pp. 201-204), or Ritwik Ghatak’s The Golden Line (pp. 205-216), among many others, not to mention texts by André S. Labarthe (as well as Martin) about Walkover (pp. 74-77), by Shigehiko Hasumi about Yasujiro Ozu (pp. 140-143) and by Jean Douchet about Kenji Mizoguchi (pp. 142-143), by Australian film scholar Ross Gibson about The Searchers (paving the way for Martin’s analysis of How Green Was My Valley, pp. 147-148), and by Jean-Pierre Gorin (as well as Raymond Durgnat) about The King of Comedy (pp. 159-161). And even if you can accept these very incomplete lists, I’ve still said nothing about Martin’s extensive treatments of contemporary television and art gallery installations, not to mention his pithy but relevant remarks about Michael Snow (pp. 82-83) .

The fact is, this highly optimistic and constructive book seeks to use “mise en scène,” whatever its past limitations (and variable meanings within separate film cultures, which the book is quite attentive to), as a sort of construction site on which to build other tools of analysis, which are outlined in the four final chapters: “Sonic Spaces,” “A Detour via Reality: Social Mise en scène,” “Cinema, Audiovisual Art of the 21st Century,” and “The Rise of the Dispositif“. At once dense and highly accessible, this 235-page book is an impassioned battle cry for the future of film art grounded in an expanded and sharpened view of its critical history. [12/29/14]