From the Chicago Reader (November 25, 2005). — J.R.

Jean Renoir, The Boss: The Direction of Actors

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jacques Rivette

With Jean Renoir and Michel Simon

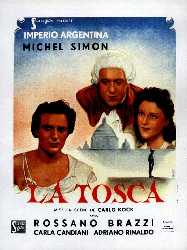

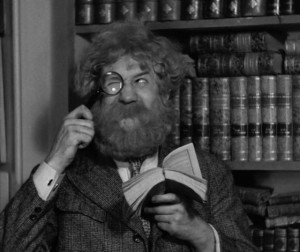

In 1966 Jacques Rivette made a three-part TV documentary titled Jean Renoir, Le patron (Jean Renoir, the Boss), and its 90-minute centerpiece has rarely been seen since. “A Portrait of Michel Simon by Jean Renoir, or A Portrait of Jean Renoir by Michel Simon, or The Direction of Actors: Dialogue,” screening on DVD this week at Alliance Francaise, is a missing link that’s key to understanding Rivette’s work. It’s a raw record of the after-dinner talk between one of the world’s greatest directors and his greatest actor, both in their early 70s, punctuated by clips from the five films they worked on together — Tire-au-Flanc (1928), On Purge Bébé (1931), La Chienne (1931), Boudu Saved From Drowning (1932), and Tosca (1941). It also includes occasional remarks by Rivette, the documentary’s producers (Janine Bazin and Andre S. Labarthe), and the stills photographer (the distinguished Henri Cartier-Bresson). The joy Renoir and Simon clearly share at being reunited is complemented by Rivette’s determination to exclude nothing, so that the “direction of actors” applies to him as much as to his two principals, each of whom can be said to be directing the other. For both Renoir and Rivette, direction requires a profound open-mindedness, alertness, and acceptance.

Don’t think you know what this documentary is doing if you’ve seen only clips from it, such as those included on the DVD of Boudu recently released by Criterion, which treats Rivette’s film as raw material to be plundered. The full version — edited by the legendary Jean Eustache (The Mother and the Whore), a post-New Wave figure as uncompromising as Renoir and Rivette — is as radical in its own way as Boudu.

Rivette made Jean Renoir, the Boss just before he transformed the style of his fiction features, and Renoir’s influence is apparent in his newfound openness to actors’ ideas. Paris Belongs to Us (1960) and The Nun (1966), Rivette’s first two features, were both meticulously scripted in advance. But in L’Amour fou (1968), Out 1 (1971), Out 1: Spectre (1972), and Celine and Julie Go Boating (1974), improvisation and chance play a major role. L’Amour fou intercuts rehearsals for a stage production of Racine’s Andromache, shot by a real 16-millimeter documentary crew headed by Labarthe, and a fictional narrative in 35-millimeter about a growing rift between the play’s real director (Jean-Pierre Kalfon) and his fictional wife (Bulle Ogier), an actress who starts to go mad after she leaves the production. Kalfon and Ogier helped develop their own characters, and in the two versions of Out 1 — a 13-hour serial made for French TV that the network refused to show and a radically different 4-hour theatrical feature edited out of it — all the actors were invited to help create their own characters and dialogue. (Rivette’s role consisted largely of arranging meetings between the characters that fit the narrative framework he’d devised and determining how to shoot these encounters.) In Celine and Julie Go Boating — lamentably, the only one of these films readily available in the U.S. — he continued to use his main actors as screenwriters, hiring another writer to help organize their input.

Celine and Julie is a transgressive comedy, as is Boudu, a film in which Simon plays a carefree, amoral, anarchic tramp in Paris. He’s saved from drowning then disastrously adopted by a liberal bourgeois bookseller, but eventually he, without regret, goes back to being a bum. Renoir and Simon fondly, even proudly, recall the shock waves Boudu produced when it first came out — some Paris viewers even ripped out theater seats. When it finally opened in the U.S. in 1967 — about two decades before Paul Mazursky did his toothless Hollywood remake, Down and Out in Beverly Hills — many people still found it shocking. At the press screening in New York the New York Times‘s Bosley Crowther, the key American gatekeeper for art movies at the time, walked out in a huff before the end and went on to complain in his review that films of this kind gave foreign-movie distributors a bad name. This was during the height of the 60s counterculture, when battle lines tended to be clearly drawn, but it’s not clear we’re more tolerant today, especially given that the 13-hour Out 1, Rivette’s greatest work, has yet to receive a single screening in the U.S. and that Criterion, the most serious DVD label handling art films, thought it was just fine to offer only snippets of his aesthetically radical documentary about Renoir.

Jean Renoir, the Boss was made during the richest period of Cinéastes de Notre Temps, a remarkable long-running French TV series devoted to filmmakers. All the best programs in this series — including ones devoted to John Cassavetes, Samuel Fuller, and Josef von Sternberg — imitated the styles of the directors, and Rivette’s program was no exception, suggesting the extraordinary freedom and generosity of Renoir. Curiously “The Direction of Actors,” unlike the more conventional installments before and after it, wasn’t broadcast on French TV at the time. I asked why when I was editing a small collection of Rivette’s writings in English translation for the British Film Institute in the mid-70s and was told it was because Simon said things that were obscene or potentially libelous. Having finally seen the film, I find this explanation ridiculous. There’s one slightly off-color joke/anecdote that’s potentially libelous — I won’t repeat it here — and it’s told by Renoir, not Simon.

I suspect one reason French TV refused to show “The Direction of Actors” in the mid-60s is the same reason it refused to show Out 1 a few years later — its style and attitude, especially its radical humanism. This film takes the position that anything a good actor says or does is automatically interesting — the same position that helped create Boudu in 1932 and Out 1 in 1971. Whether or not one agrees with that position, it’s a privilege to look through the eyes of someone who does.

When: Wed 11/30, 7:15 PM

Where: Alliance Francaise Auditorium, 54 W. Chicago

Price: $5

Info: 312-337-1070