I prefer this hard-edged comedy-drama to director Cedric Klapisch’s more sweet-tempered When the Cat’s Away, not because I’m a grouch but because the material is much denser, with half a dozen characters who surprise us at every turn. A family gathers for an acrimonious dinner in its own cafe; practically everyone treats everyone else badly, and despite a couple of faux-lyrical flashbacks we never really discover why. The mother shows more love toward the paralyzed family dog than toward any of her kids; her favorite son abuses his wife (Catherine Frot); her other son (Jean-Pierre Bacri), the family scapegoat, has recently alienated his wife; and her daughter (Agnes Jaoui) sneers at everyone, including the thoughtful waiter with whom she’s having an affair (Jean-Pierre Darroussin). This ‘Scope film won Cesars (the French equivalent of Oscars) in 1997 for best screenplay, supporting actress (Frot), and supporting actor (Darroussin), and all three were fully deserved. The screenplay is adapted from a play by Jaoui and Bacri, a couple who’ve scripted the last three Alain Resnais features, and while it isn’t bad, Klapisch and the authors haven’t fully turned it into a moviein some ways Bacri and Jaoui are more impressive as quirky actors. Klapisch hasn’t the foggiest notion of when or how to use music, but he does a fine job with the actors, and like the play itself he has a warm feeling for outcasts and a nice way of rewarding the audience for sharing those feelings. Read more

Mojtaba Raei’s episodic, three-part 1997 feature is a good example of the vital Iranian cinema our cultural gatekeepers rarely allow us to see, without the packaging and automatic charm of Gabbeh or The White Balloon but with plenty of artistic credentials of its own, a film so deeply involved in its own brand of Islamic thought that the absence of easy access to outsiders is part of its special fascination. (This is also true of Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s very bad early feature Fleeing From Evil to God, though in contrast Raei is clearly in command of the material.) Filmed in remote mountain areas of northern Iran and Azerbaijan, Birth of a Butterfly can be recommended for its landscapes, compositions, and employment of color. From the first episode, which begins with a montage of abstract rock formations leading to dwellings carved into a hillside, Raei’s choice of settings and sense of how to film them is often astonishingthough I didn’t always understand what was going on thematically or emotionally, I was held throughout by the enchantment of the natural surroundings. Ironically, the last and most comprehensible episode culminates in kitschy calendar art and a heavenly choir evoking 50s Hollywood religiosity, but prior to that I was reminded more of Alexander Dovzhenko or Sergei Paradjanov. Read more

A painfully unfunny period farce (1998) by writer-director-coproducer-costar Stanley Tucci (Big Night), though people who laugh at just about anything might be amused. In the 30s, two unemployed actors (Tucci and Oliver Platt) wind up on a luxury cruise, and the various complications call to mind Hope and Crosby fleeing from various Paramount back-lot villains. The secondary cast runs from Elizabeth Bracco, Steve Buscemi, and Alfred Molina to Isabella Rossellini, Campbell Scott, and Lili Taylornot to mention a cameo by Woody Allenand the ambience is intricately labored, stridently energetic, and about as familiar as yesterday’s toast. (JR) Read more

The Eel

An intriguing tale of moral regeneration from Shohei Imamura (Eijanaika, The Ballad of Narayama, The Pornographers: Introduction to Anthropology), adapted from Akira Yoshimura’s novel Sparkles in the Darkness. A white-collar worker spends eight years in prison after brutally murdering his wife and her lover; released to the supervision of a Buddhist priest in a small coastal town, he becomes a barber and relates almost exclusively to a pet eel he adopted while incarcerated. After saving the life of a suicidal woman who resembles his late wife, the barber makes her his assistant, yet the growing bond between them is complicated by her crazed mother and her ex-lover. The film brims over with various eccentrics (the barber’s ufologist neighbor and a former prison mate who harasses the hero and delivers drunken tirades), and Imamura views them all with mixed amusement and curiosity; he also does striking things with dream sequences and visual and aural flashbacks. At Cannes this shared the 1997 Palme d’Or with Taste of Cherry, and though I don’t consider it on the same level, it’s absorbing throughout and a good deal more accessible. Music Box, Friday through Thursday, September 18 through 24. –Jonathan Rosenbaum Read more

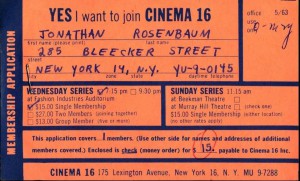

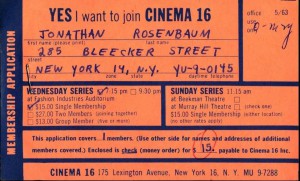

From the Chicago Reader (September 11, 1998). The illustration comes courtesy of Paul Cronin, who found it in Amos Vogel’s papers in Wisconsin. — J.R.

Talking Pictures: Scott MacDonald on Cinema 16

During its penultimate season I was lucky enough to be a member of the groundbreaking New York film society Cinema 16, where I got my first taste of Robert Bresson and Jacques Rivette. Run by Amos and Marcia Vogel between 1946 and 1963, Cinema 16 was special because it presented all kinds of “marginal” works that no one else was showing at the time. This lecture-presentation by Scott MacDonald — a specialist in independent and experimental film who’s edited a collection of scripts and three invaluable volumes of his own interviews with filmmakers — will include not only a historical account of Cinema 16’s work but a selection of remarkable shorts shown there, including Stan Brakhage’s Window Water Baby Moving (1959), Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks (1947) and Eaux d’Artifice (1953), Willard Maas’s Geography of the Body (1943), Robert Breer’s Cats (1956), and, from abroad, Arne Sucksdorff’s A Divided World (1948) and Georges Franju’s The Blood of the Beasts (1949). Franju’s film, a late addition to the program, is an extraordinary documentary about the everyday workings of a Paris slaughterhouse that manages to be shocking, lyrical, and highly moral–a good example of the great work Chicagoans almost never get to see. Read more

A serious and interesting but unsuccessful feature by Iran’s most famous woman filmmaker, Rakhshan Bani-Etemad (1997), focusing on a divorced documentary filmmaker and her teenage son. The issues broachedsuch as whether the heroine can date men without alienating her son and what makes an ideal mother (the subject of her documentary in progress, of which we see several samples)are important, but this is an issue-driven rather than character-driven film, and without fully realized characters it comes across as somewhat flat. Not even a poetic offscreen narration by the heroine, including quotes from Persian poetry, can paper over the gaps. For much of the time we’re kept deliberately distant from the charactersmany sequences consist of cars on freeways accompanied by voice-oversbut one isn’t persuaded that a closer look would teach us more. (JR) Read more

The dubious and overrated John Dahl (Red Rock West, The Last Seduction), a specialist in making reductive new versions of other people’s movies, directs a script by David Levien and Brian Koppelman that’s a tiresome rip-off of The Hustler, with poker (in a New York Russian Mafia milieu) taking the place of pool, Matt Damon taking over for Paul Newman, and John Malkovich’s scenery chewing supplanting Jackie Gleason’s self-effacement. Gretchen Mol, Edward Norton, John Turturro, Martin Landau, and Famke Janssen costar; they’re all pretty good, but not good enough to make this 1998 feature worth seeing. 121 min. (JR) Read more

This unusually charming and touching Ismail Merchant-James Ivory film feels closer to memoir than fiction; it’s drawn from an autobiographical novel by Kaylie Jones (daughter of novelist James Jones), but Ivory, working with his usual screenwriting collaborator, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, reportedly fleshed out the story with some of his own experiences. In Billy, the first of the film Read more

A potentially charming, almost fairy-tale premise for a romantic comedya Hollywood tour-bus driver (Jeremy Piven) who cruises past the homes of celebrities meets a movie star (Sherilyn Fenn) and pretends to be a screenwriter, thus ushering him into a potential romance and a taste of the local high lifeprogressively loses its air and becomes a mainly lugubrious experience because the script (by Stan Williamson) is so formulaic and threadbare. Andrew Gallerani, in his first feature as a director, does a pretty good job with the actors, but they need better material than they’re handed here. With JoBeth Williams, Alex Rocco, Jeffrey Sams, and Wallace Shawn. (JR) Read more

Another noirish heist movie stained by drippings from The Killing, The Asphalt Jungle, and, yes, Reservoir Dogs. Written by newcomer Eddie Richey and directed by English-born Danny Cannon (Judge Dredd), this boasts occasional signs of intelligence , atmosphere, and style as well as some nicely lit ‘Scope cinematography around Phoenix, Arizona, by James L. Carter (One False Move). But, alas, there’s very little forward motion. Coproducer Ray Liotta, playing a cop with gambling debts who organizes the heist, is asked to carry the whole picture on his back; he can’t be blamed if periodically it slides off. Despite some able work by Anjelica Huston, Tom Noonan, and Giancarlo Esposito, among others, the material and its inflection seem entirely too familiar. With Anthony LaPaglia, Daniel Baldwin, Jeremy Piven, and Brittany Murphy. (JR) Read more

This 1959 Doris Day vehicle, costarring Rock Hudson and Tony Randall, launched a cycle of romantic comedies predicated on her character’s chastity; Mark Rappaport unpacked its extended gay-baiting innuendo in his 1992 film Rock Hudson’s Home Movies. Compulsively mainstream as only 50s Hollywood could be, and never very funny, Pillow Talk won Day an Oscar nomination, and the story and screenplay, by Stanley Shapiro, Russell Rouse, and others, actually copped an award. Directed by Michael Gordon; with Thelma Ritter, Nick Adams, Julia Meade, Allen Jenkins, Lee Patrick, and William Schallert. 108 min. (JR) Read more

The title of Tony Gatlif’s 1997 French feature is Romany for crazy stranger; the stranger, our main point of identification, is a young scholar and music buff from France who scours the Romanian countryside looking for a legendary singer until a direct and extended encounter with Gypsy culture throws him for a loop. The third part of Gatlif’s Gypsy Trilogyafter Latcho Drom (which I revere) and The Princes (which I haven’t seen)this is a pretty good romantic comedy with neither the formal originality nor the musical excitement of Latcho Drom, though it’s certainly watchable and entertaining throughout. In French with subtitles. 121 min. (JR) Read more

The seventh Halloween film has been marketed as the last, which may actually turn out to be the case, as there’s an earnest and successful attempt to give the series a satisfying closure. Jamie Lee Curtiswho made her reputation on the first Halloween but dropped out of the series after the secondis now, 20 years later, teaching at an exclusive private school in northern California, raising a son as a single mother, and once again trying to fend off her murderously insane brother, who won’t stay dead. If you can accept the flouting of logic and credibility that usually goes with this kind of horror picture, this scary and suspenseful genre exercise, chock-full of false alarms and brutal shocks, really delivers, and Curtis approaches the assignment without a trace of condescension. Directed by Steve Miner from a script by Robert Zappia and others; with Michelle Williams, Josh Hartnett, LL Cool J, and Adam Arkin, and an amusing cameo by Curtis’s mother, Janet Leigh. (JR) Read more

Jonathan Stack and Elizabeth Garbus’s powerful documentary, winner of the grand jury prize at Sundance, focuses on six long-term inmates at the Louisiana state penitentiaryan 18,000-acre complex on the grounds of a former slave plantation, with 5,000 inmates, 77 percent of them black. It Read more

A tale of moral regeneration from Shohei Imamura, adapted from Akira Yoshimura’s novel Sparkles in the Darkness. A white-collar worker spends eight years in prison after brutally murdering his wife and her lover; released to the supervision of a Buddhist priest in a small coastal town, he becomes a barber and relates almost exclusively to a pet eel he adopted while incarcerated. After saving the life of a suicidal woman who resembles his late wife, the barber makes her his assistant, yet the growing bond between them is complicated by her crazed mother and her ex-lover. The film brims over with various eccentrics (the barber’s ufologist neighbor and a former prison mate who harasses the hero and delivers drunken tirades), and Imamura views them all with amusement and curiosity; he also does striking things with dream sequences and visual and aural flashbacks. At Cannes this shared the 1997 Palme d’Or with Taste of Cherry, and though I don’t consider it on the same level, it’s absorbing throughout. In Japanese with subtitles. 116 min. (JR) Read more